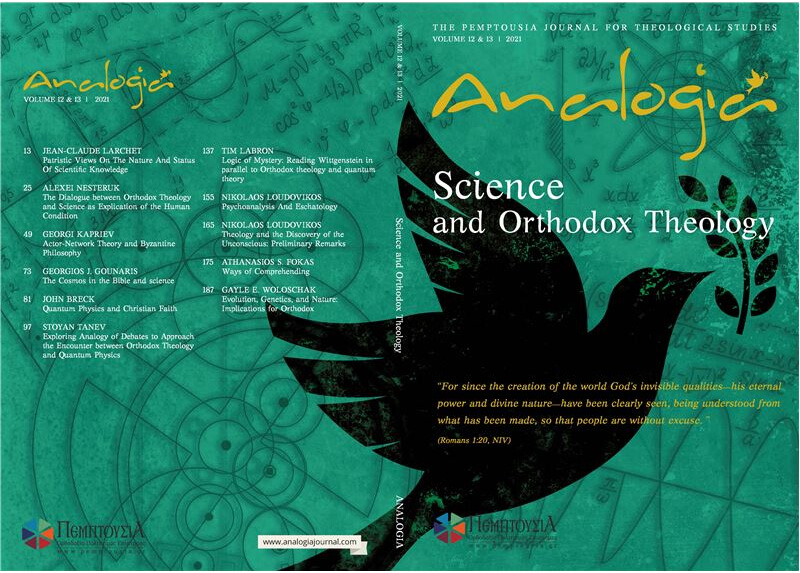

Volume 12 & 13 – Science and Orthodox Theology

For since the creation of the world God’s invisible qualities – his eternal power and divine nature – have been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made, so that people are without excuse.

(Romans 1:20, NIV)

Contents-Abstracts

Editorial

The thematic focus of this special issue is broadly defined as ‘theology and science’. The breadth of the thematic focus is part of the initial design of the special issue and could explain the variety of topics addressed by the contributors, who were invited based on their ability to contribute a unique, insightful, and engaging perspective on the productive encounter between theology and science. It should be admitted however that some of the contributions could be better positioned on the interface of science and religion (and not so much theology). This could be also considered as part of the initial editorial design which focused mainly on ensuring the interdisciplinary nature and quality of the of the specific insights.

Despite the variety of the topics, one could identify (in addition to the other distinctive topical contributions) two more dominant themes focusing on issues related to the dialogue between theology and quantum physics, and theology and psychology. The more substantial presence of these themes reminds of a point made by Christos Yannaras for whom the post-modern duty of the Church consists in the creative appropriation of the new language emerging quantum mechanics and post-Freudian psychology, aiming at linking the salvific message of the Christian Gospel to linguistic categories that could be more efficient in the interpretation of the reality of existence, the appearance and disclosure of being, and more specifically, in the articulation of the existential and empirical mode of the relationship between God, world, and man.1 These two themes however could only enhance the interdisciplinary value of the rest of topics discussed in the special issu… Continue Reading

The thematic focus of this special issue is broadly defined as ‘theology and science’. The breadth of the thematic focus is part of the initial design of the special issue and could explain the variety of topics addressed by the contributors, who were invited based on their ability to contribute a unique, insightful, and engaging perspective on the productive encounter between theology and science. It should be admitted however that some of the contributions could be better positioned on the interface of science and religion (and not so much theology). This could be also considered as part of the initial editorial design which focused mainly on ensuring the interdisciplinary nature and quality of the of the specific insights.

Despite the variety of the topics, one could identify (in addition to the other distinctive topical contributions) two more dominant themes focusing on issues related to the dialogue between theology and quantum physics, and theology and psychology. The more substantial presence of these themes reminds of a point made by Christos Yannaras for whom the post-modern duty of the Church consists in the creative appropriation of the new language emerging quantum mechanics and post-Freudian psychology, aiming at linking the salvific message of the Christian Gospel to linguistic categories that could be more efficient in the interpretation of the reality of existence, the appearance and disclosure of being, and more specifically, in the articulation of the existential and empirical mode of the relationship between God, world, and man.1 These two themes however could only enhance the interdisciplinary value of the rest of topics discussed in the special issue.

For example, Jean-Claude Larchet, a well-known French Patristic scholar, Orthodox theologian and prolific writer, provides a systematic review and analysis of The Patristic Views on the Nature and Status of Scientific Knowledge. According to Larchet, even though some of the Fathers admit the possibility of using reason or logical reasoning in the theological domain, the common Patristic view is that science remains limited to a knowledge of appearances only. For Larchet however this view does not seem to contradict the current scientific understanding since science focuses on studying phenomena, i.e. it does not claim that its knowledge coincides with reality as it is in itself, and the deepest essence of things remains inaccessible to the scientific approach. For some of the Fathers true knowledge of the nature of things is that of their logoi. Such knowledge becomes possible through the contemplative function (θεωρία) of the intellect (νοῦς), which presupposes a proper spiritual preparation (ἄσκησις). This contemplation seeks to grasp the logoi of created beings in themselves by disengaging them from their immediate sensible expression, and thus distinguishing in every single being between its logos and its appearances. Natural contemplation discovers God, the incarnate Logos in the logoi of beings, but it also discovers the Spirit that is present in creation. This is how a believer can attain spiritual knowledge while the contemplation of nature is related to the science of beings alone.

Alexei Nesteruk is a Senior Research Lecturer in the School of Mathematics and Physics at the University of Portsmouth, Hampshire, GB, working on foundations of cosmology and quantum physics. He is one of the most proactive Orthodox contributors to the dialogue between science and theology. Nesteruk re-envisions The Dialogue between Orthodox Theology and Science as Explication of the Human Condition. He adopts a philosophical perspective in emphasizing that the founda- tion of both science and theology originates in human beings. Human beings have an ambiguous position in the universe that cannot be explicated on metaphysical grounds but can be interpreted theologically. The difference in the hermeneutics of representation of the world in the phenomenality of objects and the inaugural events of human life and religious experience is a key characteristic of the human condition. This difference is the reason for the paradoxical position of humanity as an object in the world and a subject for the world. It is also the fundamental reason for the split between science and theology. That is why, for Nesteruk, any attempt of overcoming this difference under the guise of a ‘dialogue’ between science and theology represents an existentially untenable enterprise. The overcoming of the unknowability of man by himself which is attempted through the reconciliation of science and theology, is not ontologically achievable, but demonstrates the possibility of uncovering a definite sense of purpose. In this sense, the dialogue between theology and science can be considered as a teleological activity representing an open-ended hermeneutics of the human condition. For Nesteruk the discourse of the paradox of subjectivity provides the delimiters for any of such hermeneutics.

Georgi Kapriev is Professor of the History of Philosophy at St. Kliment Ohridski University in Sofia, Bulgaria. The area of his research interests is the medieval—Latin and Byzantine—philosophy and culture, as well as the cultural history of the 20th and 21st centuries. Kapriev’s works have advanced the study of Byzantine philosophy worldwide. His paper Actor-Network Theory and Byzantine Philosophy offers a detailed reflection on almost 20 years of work focusing on the interdisciplinary exploration of the paradigm of Actor-Network-Theory (ANT) through the application of concepts and methods inherent in Byzantine philosophy. Kapriev systematizes and expands some of the latest research in this interdisciplinary domain. The starting point is the attempt to re-examine the sociological explanations of such phenomena as endurance, resistance and innovation, which are difficult to explain through the paradigms of classical sociology. The suggested analysis adopts the concepts of essence-energy-power, hexis, perichoresis, hypostasis, prosopon and body, to refine some of the positions characteristic of the ANT paradigm, and propose new ones that allow to problematise ANT’s principle of symmetry between human and non-human actors, the understating of initiative, the essence and the figure of the actor. The paper pays special attention to some of the paradoxes inherent in the understanding of the human hypostasis and to the questions emerging from the theoretical prescriptions of transhumanism. It is a great example of how the adoption of the conceptual apparatus of Byzantine theology could benefit the social sciences.

Fr. John Breck is an Archpriest and theologian of the Orthodox Church in America specializing in Scripture and Ethics. He has served as Professor of New Testament and Patristics at St. Herman’s Orthodox Theological Seminary (Kodiak, Alaska), as Professor of New Testament and Director of Studies at St. Sergius Orthodox Theological Institute (Paris, France), and as Professor of New Testament and Ethics at St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary (Crestwood, New York). His paper Quantum Physics and Christian Faith is a text adapted from a chapter of his recent book Beyond These Horizons, Quantum Physics and Christian Faith, published in 2019 jointly by St. Sebastian Press and Kaloros Press. The book itself is structured as a novel, with lectures given by a young professor of physics to a group of alumni of his university. It lays the groundwork for an exploration of the relationship between quantum mechanics and certain key aspects of the traditional Christian teaching. According to Fr. John Breck quantum theory, if properly interpreted, offers invaluable insights in our quest to see beyond the empirical horizons of the world we live in. “It provides a fresh perspective on the spiritual significance of the Whole, from unimaginably small quantum phenomena to the immense galaxy clusters of an ev- er-expanding universe.” One of the aims of the book is to point out that our usual conceptions of God and the world are simply inadequate. With the help of insights drawn from quantum theory, we can now see that Creation is more intricate, more interconnected and more beautiful than one could ever have imagined. The text included in this special issue demonstrates how a deeper discussion of the peculiarities of quantum physics could be turned into a wonderful journey into the realm of Orthodox theology.

Stoyan Tanev is Associate Professor of Technology Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management in the Sprott School of Business at Carleton University, Ottawa, Canada, and Adjunct Professor in the Faculties of Theology at St Paul University in Ottawa and Sofia University, Bulgaria. He holds a PhD in Physics and a PhD in Theology. His paper Exploring Analogy of Debates to Approach the Encounter between Orthodox Theology and Quantum Physics adopts the Analogical Comparative Theological Approach (ACTA) to explore the encounter between Orthodox theology and quantum physics. The ACTA approach integrates the intuitions of the analogical isomorphism and comparative theology methods by focusing on issues that are of high relevance for both theology and physics. The issues addressed here are the ones emerging within the context of two important debates: a) between St Gregory Palamas and Barlaam the Calabrian in the fourteenth century, and b) between Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr in the twentieth century. The first debate is refers to some of the key aspects of Orthodox theology and spirituality. The second debate is related to the never-ending challenges of the interpretation of quantum mechanics and the nature of physical reality. The analysis suggests that the controversial issues in the two debates are deeply rooted in disagreements about the nature of knowledge, the interplay between epistemological and ontological issues, the challenges of applying logical arguments, the role of apophaticism, the challenges of knowing and the ways these challenges affect the interpretation and sharing of human experience. The discussion of the role of apophaticism is of particular interest since it shows a common need of going beyond representation, assertion and negation by focusing on epistemological conditions of knowledge emerging through union and participation. This need is more sharply expressed in Orthodox theology where the apophatic does not emerge as a comment on representation, but as an opportunity for participation. The paper offers a first theological reflection of the analogical potential of QBism—a recent interpretation of quantum mechanics that takes agent’s actions and personal experience as the central concerns of quantum theory. The key message of the paper is that one can learn more about theology and quantum physics by adopting the ACTA exploratory lens to examine the potential similitudes between the ways theologians and physicists debate about their ways of knowing and the challenges of articulating their personal experience with reality.

Tim Labron is Professor of Philosophy and Religious Studies in Concordia University of Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. Labron is a leading scholar working on the theological implications of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s philosophy. One of his last books is Science and Religion in Wittgenstein’s Fly Bottle (Bloomsbury Academic, 2016). His paper is titled Logic of Mystery: Reading Wittgenstein in Parallel to Orthodox Theology and Quantum Theory. Labron’s starting point is that, in contrast to Western philosophy, theology, and classical physics, Wittgenstein, Orthodox theology, and quantum theory (e.g., Bohr and the Copenhagen interpretation) are more comfortable with mystery and do not have a similar drive to explain, codify and justify knowledge. According to Labron, these three points of view—Wittgenstein, Orthodox theology, and Bohr—are distinct from one another, yet they all converge on the importance of our living experience (participation) in contrast to excessive ratiocination. At the same time, it is obvious that neither Bohr nor Wittgenstein were opposed to scientific investigation, nor by any stretch of the imagination were they Christian apologists. Yet they both showed the confusion of conflating or reducing reality and meaning to metaphysical or logical confines only. Labron’s point is that mystery is a given and in a theological context it is experienced as a personal relationship. The example provided by Labron refers to the liturgy—mystery is part of the liturgy, but it is not a cognitive metaphysical mystery. It is exactly because mystery is part of the liturgy, it is concretely lived by the believers.

Georgios Gounaris is Professor Emeritus in the Department of Theoretical Physics, Aristotle’s University of Thessaloniki. His paper The Cosmos in the Bible and Science presents the Biblical description of the Creation of the Cosmos in parallel with the corresponding description of contemporary science. The scientific under- standing of Creation presented in the paper is based on the assumption that the forces of Nature were created at the very beginning and have remained unchanged ever since. First, without this assumption, it is impossible to shape a creation story. Second, the few available measurements so far agree with this assumption. Gounaris switches masterfully between the biblical and scientific narratives to offer a story which is both very readable and highly insightful.

Fr. Nikolaos Loudovikos is one of the leading Orthodox theologians today who has an interdisciplinary background in theology, philosophy and psychology. He is a Professor of Dogmatics and Philosophy at the University Ecclesiastical Academy of Thessaloniki (Greece), Visiting Professor at the University Balamand (Lebanon), the Institute for Orthodox Christian Studies (Cambridge, UK), and Research Fellow at the University of Winchester in the United Kingdom. Loudovikos’ paper Psychoanalysis and Eschatology provides an insightful discussion of the relationship between psychoanalysis and theology. According to Fr. Nikolaos, at the deeper level of ontological presuppositions and consequences, psychoanalysis has yet to receive a proper theological treatment or be given a sufficient and sober interpretation. He engages in a discussion of several philosophical critiques as a path towards a theological hermeneutical encounter. Loudovikos selected three of the most important philosophical critics of psychoanalysis in the twentieth century: L. Wittgenstein, P. Ricoeur, and C. Castoriadis, because of the complementarity of their critiques and their suitability for a potential theological hermeneutical engagement. After dis- cussing their views, Loudovikos asks the question: In what way, then, does psychoa- nalysis differ from theology? The answer he provides is provocative: “psychoanalysis seems to be at its base a former philosophy that wishes to become a theology, and herein lies its fundamental ‘scientific character’”. According to Fr. Nikolaos, it is the ‘theological’ nostalgia for empirical authenticity that provides psychoanalysis with the quality of an empirical science. The paper offers an insightful story that could benefit many scholars interested in the interface of psychology, philosophy and theology.

In his second paper Theology and the Discovery of the Unconscious: Preliminary Remarks, Fr. N. Loudovikos provides a theological account of the Unconscious by reviewing some of the most relevant research studies in the domain, and then making several theological remarks as a basis for future studies. He reviews the contributions of three books: Matt Ffytche’s The Foundation of the Unconscious: Schelling, Freud, and the Birth of the Modern Psyche; Suzanne Kirschner’s The Religious and Romantic Origins of Psychoanalysis: Individuation and Integration in Post-Freudian Theory; Michel Henry’s emblematic Généalogie de la Psychanalyse: Le Commencement Perdu. The combination of the three books forms a highly representative source for the research of the Western history of the Unconscious. Loudovikos guides the reader through the insights articulated in these works and ends his analysis by articulating several preliminary remarks. First, for him, the Unconscious seems to relate with the truth and the fullness of human nature and life, but the relation is impossible without its grounding in appropriate theological premises such as freedom and autonomy, holism, catholicity, particularity, originality. Second, the Unconscious has to do with human desire and will, and therefore with ecstasis, which means that the discernment of similarities and differences concerning its possible meaning requires a history of ecstasis in both East and West. A possible theological interpretation of the Unconscious could find its basis in St Maximus the Confessor’s understanding of the natural will, who can be considered as a forerunner of the modern notion of the Unconscious. Third, the Unconscious is apophatic; it is radically unknowable but pretends to possess an absolute knowledge concerning the essence of human nature. To reconcile the bipolarity of unknowability and knowledge in the Unconscious one should find a true analogical dimension that could relate the divine fullness and human inwardness. Loudovikos suggests that his previous work on the analogical identity of man could become a basis for further exploration of this point. Fourth, the Unconscious is wise because it goes beyond representation but also because it reflects primordial human nature and life. Because of that it can be related with the image of God in man. Fifth, the Unconscious is revealing because it discloses hidden aspects of the divine image. Lastly, because of its revealing role, the Unconscious is also eschatological, in the sense that in its theological and psychological interpretations it pertains to the final fulfilment of human nature. According to Loudovikos, it will be impossible to explore the notion of the Unconscious in its fullness unless one examines further the relation and the difference between the ancient philosophical and Patristic concepts of life, nature, person, and ecstasis.

Athanasios Fokas is a mathematician, with degrees in Aeronautical Engineering and Medicine. He is Professor of Nonlinear Mathematical Science in the Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics (DAMTP) at the University of Cambridge. His paper is the Prologue of his forthcoming book Ways of Comprehending(World Scientific, 2022). In this book Fokas suggests a unifying approach to life that is based on the elucidation of deep neuronal mechanisms, which ultimately lead to understanding and fulfilment. The book is an exemplary work of interdisciplinarity. Some of its key features are as follows: (i) it suggests a way for resolving the paradox between the abundance of information and specialization; (ii) it introduces an all-en- compassing approach to the sciences and humanities that will help restoring the arts and letters to their rightful position at the centre of the human existence; (iii) it demonstrates that a unified, integrative approach to knowledge is indeed possible by refuting the myth that it is supposedly impossible to be both deep and broad (for the author breadth and depth are not antithetical but act synergistically); (iv) it provides the proper framework for an illuminating discussion of several important questions which should concern every educated individual: “What is the origin of the distinguishing mental advantages of humans in comparison to our evolutionary predecessors? What is the relationship between innate and acquired knowledge? What does it mean to ‘understand’ and how is insight achieved? Why is it possible for us to comprehend the universe? What is the effect of the cultural evolution on our brains? What is the neuronal origin of our emotional responses to arts and letters?” The paper will provide a sense of how the answers to these questions should incorporate elements of biology, neuroscience, medicine, mathematics and physics.

Gayle E. Woloschak is a Professor of Radiation Oncology at Northwestern University in Chicago and Associate Director for the Zygon Center for Religion and Science at the Lutheran School of Theology Chicago. She holds a PhD in Medical Sciences and DMin in Eastern Christian Studies. Woloschak’s paper Evolution, Genetics, and Nature: Implications for Orthodox provides a medical scientist’s perspective on evolution. It does not engage in the usual for the science and religion community apologetics of evolution—i.e., defending evolution against creationism or intelligent design or some other form of fundamentalist perspective on human origins. It attempts to discuss evolution from the perspective of the implications it has for how we think about humanity now and in the future. Unavoidably, the suggested perspective has a naturalistic flavour which refers to life as ‘that which evolves’ and defines evolution as a process by which natural selection chooses those species that are most fit to survive in their current environment. Evolution is driven by random mutations. According to Woloschak the randomness of mutations is essential for evolution because without randomness species would not be able to adapt to a changing environment and the Earth could not sustain life. She admits that many in the Church find it worrisome that randomness plays such an important role in creation. Randomness however allows for a creative and dynamic component in the process of creation and is essential not only for the evolution of species but also for the survival of each living organism. The concept of natural selection suggests that nature selects for an organism what is best suited for a particular en- vironment, which does not mean that this is the best possible design that one could develop or the best organism that lives in an environment. Evolution, because of its randomness, is not perfect. Life is not perfect, and many aspects of humanity are not well-suited to the lives we live. But in all cases our biological existence is the result of our species’ evolution so far. Woloschak raises two questions: How much humanity should be revering our evolution and calling those biological traits that have been most successful so far ‘natural’? Should we morally forbid anything that appears to be ‘unnatural’ today simply because it was not (yet) selected for by evolution? The paper discusses the possible answers to these questions in the context of the Church and provides a reflection on their implications for the emerging ethical perspectives on ‘un-natural acts’ such as in vitro fertilization (IVF), genome editing, vaccines, and other medical technologies. The final recommendation of Gayle Woloschak is that people in the Church should remember two important aspects of evolution. “First — we are all members of our species and a new disease without a vaccine or swift climate change may quickly change the odds for survival of those of us who are currently in majority. Secondly — we recognize as ‘natural’ simply that which is currently most prevalent in our species because evolution has favored it so far.” The paper is quite informative. It opens the possibility for future studies that could focus on the discussion of some important theological issues such as the relation between the evolution and the human Fall, as well as the relation between the characteristics of the Divinely created human nature, its imperfections from the point of view of evolution, and the understanding of the ‘natural’ which seems to emerge somewhat a-theologically, i.e. predominantly in the context of contemporary medical profes- sional practice.

We hope that the specific topics and interdisciplinary perspectives adopted by the contributors to this special issue will both enable, motivate and demonstrate the need for future studies that could help in shaping the answers to some important questions. What does make the dialogue between science and religion theologically valuable? What are the best modes of engaging theology and science in a way that could enable their synergetic impact on each other? How can we transform our academic endeavours on the interface of theology and science into a source of prayer, hope, compassion, and love towards the Other? How to use the dialogue between theology and science as an invitation for the participatory engagement and theological opening of people who are outside of the Church?

– Stoyan Tanev, Special Editor

1.

See Christos Yannaras, ‘The Reality of the Person in Post-Modernity’, in: The Meaning of Reality – Essays on Existence and Communion, Eros and History (Los Angeles: Sebastian Press & Indiktos, 2011), 21- 28, as well as interview with Yannaras on June 26, 2002 at the Bulgarian Science and Culture Foundation in Sofia, Bulgaria (in Bulgarian): http://svetinikolay-so a.info/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/www.hkultura. com_db_text_2002_3_4_cristosjanaras.pdf.

Logic of Mystery: Reading Wittgenstein in parallel to Orthodox theology and quantum theory

Theology and philosophy are predominately found within an analytical context, that is, a context within which a ‘rigorous’ system of thought is built from one element to another element. In parallel fashion, the same can be said regarding classical physics and its mechanical casual movement from one point to another point. Yet there are voices stepping out of these systems and moving towards a more ‘living’ thought. The move toward the ‘living’ can be found in post-classical physics with the inclusion of the observer, but long before this shift in physics there is the long standing Orthodox theology, and in between there are well known yet often misunderstood philosophers, such as Ludwig Wittgenstein. These ‘living’ voices want to draw us away from inert abstract systems back to ourselves and thereby back to humanity.

Introduction

Why is there a seemingly insatiable desire for templates behind our lives to secure knowledge, the ultimate physical building blocks of reality, causality, and perhaps even determinism? This yearning consumes much of Western philosophy, theology, and science; and frequently Aristotelian logic drives this mode of thought. There is no question regarding the general value of such logic, but to what extent can it be questioned? Archbishop Lazar Puhalo certainly does bring questions when he states: ‘The Platonism and quasi-Gnosticism of Augustine of Hippo distorted theology in the West into a system of philosophical speculation, and forever separated it from the existential, living theology of Orthodox Christianity’.1 Likewise, as noted by Léon Rosenfield in conversation with the Japanese physicist Hideki Yukawa: ‘I asked Yukawa whether the Japanese physicists had the same difficulty as their Western colleagues in assimilating the idea of complementarity … He answered “No, Bohr’s argumentation has always appeared quite evident to us;… you see, we in Japan have not been corrupted by Aristotle”’.2

Certainly, in our daily lives it can be very useful to check a barometer and a thermometer. We see the air pressure and temperature falling, dark clouds forming in the sky, and decide that there is a good reason to bring one’s jacket and umbrella

Archbishop Lazar Puhalo, The Evidence of Things Not Seen: Orthodoxy and Modern Physics (BC, Canada: Synaxis Press#, 2013), 16.

Léon Rosenfeld, ‘Niels Bohr’s Contribution to Epistemology’, Physics Today 16 (1963): 47.

Evolution, Genetics, and Nature: Implications for Orthodox

In the science-religion community much effort is placed on doing ‘evolution apologetics — i.e., defending evolution against creationism or intelligent design or some other form of fundamentalist perspective on human origins. This article will not engage in the usual apologetics as that has been done elsewhere (1–3) in depth.1 Instead, this work will attempt to discuss evolution from the perspective of the implications it has for how we think about humanity now and in the future.

Life Is at Which Evolves

There are many definitions of life—that which is capable of reproduction, that which can metabolize, etc. One definition that seems fitting in this article is ‘that which evolves’. Evolution was first defined in biology as a process by which natural selection chooses those species that are most fit to survive in their current environment. Biological evolution also implies that survival will permit procreation where the next generation will largely resemble the parental organism(s) that survived. The conveyers of evolution are genes, fragments of DNA that code for proteins that function in cells. Changes in genetic material are called mutations. On the level of organism, mutations can be beneficial, harmful, or neutral. Mutations can be beneficial in one environment and harmful in another. At the same time, mutants that are neutral (i.e., convey no advantage or disadvantage in a given environment) remain in the population in silence…and yet at some future time, these neutral mutations could become advantageous or problematic.

On Planet Earth, life became life when I became capable of evolving.2 It is not known if this is the same on all planets (if there is life on other planets), but on this planet evolution is a pre-requisite for life. Evolution is a natural process, but it is also the reason for other ‘natural’ processes. Humans reproduce by sexual reproduction because evolution selected for it, and many species reproduce by asexual reproduc-

G. E. Woloschak, ‘The Compatibility of the Principles of Evolution with Eastern Orthodoxy’, in. St. Vladimir’s Theological Quarterly 55 (2011): 209–31; Gayle E. Woloschak, ‘God of Life: Contemplating Evo- lution, Ecology, Extinction’, in The Ecumenical Review 65.1 (2013): 145–59.

Much of the description about evolution comes from textbook and Wikipedia information about evolution. One of the best evolution textbooks is D. Futuyama and M. Kirkpatrick, Evolution (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2018). Wikipedia also has a variety of different websites with accurate information on evolution, mutations, etc.

Ways of Comprehending

This paper is the Prologue of the forthcoming book Ways of Comprehending, by A.S. Fokas (World Scientific, 2022): This book is dedicated to my three children and to all young people in the hope that it will offer them the happiness and personal fulfilment that follows from acquiring an understanding of the origin of their thoughts, feelings, and actions.

The search for understanding gives rise to deep admiration for the immense wisdom and beauty of Nature, and in particular for its greatest achievement: the human brain. Writing this book, I felt deep sense of gratitude for the privilege of being able to enjoy a plethora of complex and multifaceted creations of Nature and humanity. I hope, and expect, that those who read this volume will experience similar feelings.

‘Unification’ and ‘analogical thinking’ are central themes of this book. In this connection, it is worth noting that the completion of the formalism that unifies the four fundamental forces of nature, the gravitational, electromagnetic, weak, and strong interactions, still stands as the holy grail of physics. By analogy, it is natural to attempt to integrate the biological and cultural ‘forces’ dictating life. In this volume, an effort is made to explore this unification.

By analysing fundamental neuronal mechanisms, it will become clear that the human brain is predisposed to seek knowledge and beauty, without the artificial distinction between sciences and humanities. It is argued that such a grand quest requires an interdisciplinary, integrative approach. Furthermore, it is suggested that this search is facilitated by employing the notions of cognition, computability,creativity, and culture. The necessity for such a unified approach follows from the insight that everything is related to everything else. Perhaps no one expressed this fact better than Leonardo da Vinci, the embodiment of interdisciplinarity:

‘Study the science of art. Study the art of science. Develop your senses—especially learn how to see. Realize that everything connects with everything else’.

A crucial part of an interdisciplinary approach to knowledge and culture is the appreciation that life generously provides many sources of pleasure and satisfaction, beyond the utilization, efficiency, power, and beauty of technological creations. Indeed, in life there also exists that which, according to Ludwig Wittgenstein, ‘cannot

Theology and the Discovery of the Unconscious: Preliminary Remarks

The most recent relevant discussion seems to involve, perhaps unavoidably, a theological account of the Unconscious, which lies behind almost all concepts on the adoption of which concepts psychoanalysis depends. In the present paper I will limit myself to studying some important books that show the current status of relevant research, and then I will attempt to offer some more, though still preliminary, theological remarks.

In my book entitled Psychoanalysis and Orthodox Theology: On Desire, Catholicity, and Eschatology,1 I ventured to search for the uncovering of a possible spiritual dimension of psychoanalysis that somehow ‘correlates’ with fundamental theological notions. For this purpose, I confined myself to what are in my view three of the most important and common concepts, considered bridges between theology and psychoanalysis: First, that of Desire as it is described in its subjective functioning according to Lacan, or, in theological terms, of natural will (as formulated by St Maximus the Confessor), which has to be rooted in nature as an expression of its internal life , instead of being just a vehicle of the intellect. In this way it can express human desire as the pure yearning for unity, both internal and external, which can hold all things together, an ontological unity that can be properly expressed by the theological notion of consubstantiality.2

Second, the concept of Catholicity, which I called ‘Inter-Intra-co-Being’, developed as a theological commentary on the psychoanalytic experience of inter-subjectivity, where the pan-unity of all things (co-being) takes place within the

Αθήνα: Αρμός, 2003.

Regarding the concept of consubstantiality, see in my book Analogical identities: The Creation of the Christian Self. Beyond Spirituality and Mysticism in the Patristic Era, (Turnhout: Brepols, 2019), 183: ‘The achievement of the of nature is, of course, the work of Christ, who draws together the ontological gaps which segment the relationship of created things between themselves and God, effecting this thereafter in the Church through the mysteries, as “Eucharistic Ontology” of the entry from now of beings into the last things of the Kingdom. As regards the will, from the point of view of the believer, the manner in which this consubstantiality emerges, which Christ Himself activates eucharistically in the Holy Spirit, is a bond of the personal will towards others, as a relationship “bringing all, through the one logos of creation to the one cause of nature” (Maximus the Confessor, To Thalassius, PG 90, 724C-725A), i.e. to consubstantiality’ .

Psychoanalysis And Eschatology

After the arrival of psychoanalysis, nothing has remained untouched by it, and this is even more the case if we add Freud’s meta-psychological ambitions, which sought to explain even more broadly the phenomena present in the individual soul, such as culture, religion, art, etc. Theology in particular felt directly threatened by Freud’s militant atheism. Despite this fact, however, I would still hazard saying that at the deeper level of ontological presuppositions and consequences, psychoanalysis has yet to receive proper theological treatment or be given sufficient interpretation.

Theological Hermeneutics and Depth Psychology1

A century after the publication of the first edition of The Interpretation of Dreams(1900), it would merely be to repeat a truism to claim today that not only the method of investigation of psychoanalysis but also its terminology have come to permeate the whole of Western humanistic thought, a unique phenomenon in the intellectual history of the modern period. Despite initial objections, the new Freudian ‘science’ has proved to have established itself not only in the realm of experts but in the common perception of modern man about himself. The popularisation of psycho- analysis has already produced a veritable mythology about the soul, and it is not at all rare to hear terms taken from the first and second Freudian local description of the psyche thrown around in public as common sense and self-evident.

At the same time, much water has flown since then in the river once carved out by Freud. Many of his views have been reconsidered, and ‘depth psychology’ is now carried along countless new hermeneutical channels and ‘schools’, none of which can lay claim to very great success in their attempts to develop the ‘science of the unconscious’. Of course, there has been no lack of attempts to ‘return to Freud’ and his ‘holy’ texts, usually of varying levels of inspiration and accompanied by radical hermeneutical revisions, either at the level of theory or of clinical practice, which is only natural given that the latter constitutes the goal of the former.

A paper given at the International Conference ‘Orthodox Theology and Psychotherapy’ in Aliartos, Greece on 1–5 October 2003. Published in Greek, as part of my book Psychoanalysis and Orthodox Theology: on Desire, Catholicity, and Eschatology, (Αθήνα: Αρμός, 2003). Translated in English by Vincent DeWeese.

Exploring Analogy of Debates to Approach the Encounter between Orthodox Theology and Quantum Physics

This article adopts the Analogical Comparative Theological Approach (ACTA) to explore the encounter between Orthodox theology and quantum physics. The ACTA approach integrates the intuitions of the an- alogical isomorphism and comparative theology methods by focusing on issues that are of high relevance for both theology and physics. The specific issues addressed here are the ones emerging within the context of two important debates: a) between St Gregory Palamas and Barlaam the Calabrian in the fourteenth century, and b) between Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr in the twentieth century. The first debate refers to some of the key aspects of Orthodox theology and spirituality. The second debate is related to the never-ending challenges of the interpretation of quantum mechanics and the nature of physical reality. The analysis suggests that the controversial issues in the two debates are deeply rooted in disagreements about the nature of knowledge, the interplay between epistemological and ontologi- cal issues, the challenges of applying logical arguments, the role of apophaticism, the challenges of knowing and the ways these challenges affect the interpretation and sharing of human experience. The discussion of the role of apophaticism is of particular interest since it shows a common need of going beyond representation, assertion and negation by focusing on the epistemological conditions of knowledge emerging through union and participation. This need is more sharply expressed in Orthodox theology where the apophatic does not emerge as a comment on representation, but as an opportunity for participation. The fundamental presupposition of the article is that one can learn a lot about theology and quantum physics by adopting the ACTA exploratory lens to examine the potential similitudes between the ways theologians and physicists debate about their ways of knowing and the challenges of articulating their personal experience with reality. One of the key benefits of the suggested approach is its ability to examine similitudes between two so different domains of human experience – one based on Divinely revealed knowledge, the other on the proactive and dialogical human engagement with the deepest layers of physical nature. The study does not pretend to be conclusive. It should be considered as part of an ongoing reflection on the value of exploring the encounter between theology and physics.

Patristic Views On The Nature And Status Of Scientific Knowledge

The Fathers have a variable approach to science. Science is often respected in its own method and in the knowledge that comes from it. Medical science, for example, was recognized very early in its autonomy. A Father like St Gregory of Nyssa, in the fourth century, had no difficulty in recognizing Hippocratic-Galenic medicine despite its pagan origin. For his part, St Gregory Palamas, in the fourteenth century, does not hesitate to affirm: ‘In matters of physiology, there is no dogma’, a liberal position, but only in appearance, because there is in the background the idea that scientific knowledge is relative and should be relativized as a mode of knowledge. If some Fathers admit the possibility, up to a certain point, of the use of reason (St Maximus the Confessor) or of logical reasoning (St Gregory Palamas) in the theological field, it is however commonly accepted that science remains limited to a knowledge of appearances only. This does not contradict the conception that current science has. On one hand, it defines itself as the study of phenomena (τα φαινόμενα, that is to say what appears to the senses or to the instruments of observation and measurement) and of their laws. On the other hand, the neo-Kantian conception of modern science, considers that the scientist knows reality only as it appears to him or her and as he or she theorizes it by reason. Then, science is not able to claim that knowledge, always relative, coincides with reality as it is in itself, the essence of being remaining forever inaccessible to this type of approach. From this point of view, some Fathers stress that the true knowledge of the nature of things is that of their logoi (St Maximus the Confessor), which is only possible by the intellect (νοῦς) in its contemplative function (θεωρία), which presupposes a whole spiritual preparation (ἄσκησις). Compared to this form of superior knowledge, scientific-type knowledge is, in the eyes of some Fathers (Isaac the Syrian) only a degenerate form of knowledge, implemented by fallen man as an ersatz to true spiritual knowledge, which he has lost and cannot easily recover.

Introduction: Some remarks on methodology

The subject I have chosen to deal with brings up some methodological problems that need to be examined.

The first problem has to do with the idea of ‘scientific knowledge’ and therefore of ‘science’ itself. In this presentation, we understand the word science, a priori, in its modern, ordinary sense, that is, the commonly accepted definition: ‘knowledge of phenomena and their laws’, a rational, rigorous, coherent knowledge that, from the methodological point of view, implies in principle three stages: 1) observation,

Quantum Physics and Christian Faith

“Traditional” or “Orthodox” Christianity is founded on the conviction that God exists in the paradoxical state of “infinitely distant” yet “closer to us than our own heart.” That state is characterized by “superimposed” and “entangled” conditions that involve antinomies: God as both One and Three; Christ as both God and man; the Church as a fallen earthly institution and as a source of divine grace and life, etc. This article demonstrates the analogous relationships that exist between such elements of Christian faith and the domain of quantum mechanics. The presence and activity of God are seen in a new perspective, shaped by recent scientific discoveries concerning the microcosm. The world of the “very small” holds the key to a perception of God that reveals both His continuing creative work and His ineffable mystery.

Introduction

This text is adapted from a chapter of the book Beyond These Horizons. Quantum Physics and Christian Faith, published jointly by St. Sebastian Serbian Press, Alhambra, CA, and Kaloros Press, Wadmalaw Island, SC., 2019. The book itself is structured as a novel, with lectures given by a young professor of physics to a group of alumni of his university.

God beyond Reality

A prayer in the Orthodox Christian tradition describes the Holy Spirit as ‘everywhere present, filling all things’. It is that Spirit, who creates and sustains the underlying Reality—the transcendent Force or Field—that gives birth to both the virtual and the actualized aspects of the world we live in. Genesis declares that at the creation the Spirit ‘moved across the face of the waters’, bringing order, harmony, and beauty out of primeval chaos. That is, the Spirit ‘realizes’ or ‘actualizes’ the cosmos (from which we get our word ‘cosmetic’, implying order and beauty). In a Biblical perspective—the perspective held by traditional Christianity, based on individual and communal experience—the Spirit of God is the Spiritus creator, who relates to his creation in personal terms, terms of communion and love. This does not contradict the Biblical affirmations regarding the creative activity of Christ, the Son (Jn 1:3; Col 1:16; Heb 1:2–3), but rather complements them. Together with the Second Person of the triune Godhead, the Spirit creates, shapes, and directs all of reality toward its final end, which is eternal participation in divine Life (Rom 8:5–11). This is a trinitarian perspective.

The Cosmos in the Bible and science

In this article I present the Biblical description of the Creation of the Cosmos in parallel with the descrip- tion of contemporary science. The first part deals with the events that started the whole Universe. These are the events that took place during the first day of the Bible and the night that followed it. The first day begins with darkness, which is subsequently dissolved by a bright light that initially shines like in a hot summer noon. In the sequel, this light evolves and eventually disappears through an impressive evening, after about twenty million years. Then comes the first night that ends after about nine billion years, with the emergence of the primitive Earth. The second part of Creation describes how an earth observer would have viewed the formation of the Earth and its waters and the appearance of the living beings and man. The second to the sixth days appear to be merely long periods of time. They do not have a day-night structure like the first day.

The scientific understanding of Creation perceptions I am presenting here is based on the assumption that the forces we see today in Nature were created at the very beginning and have remained unchanged ever since. If we do not make this assumption, we cannot say anything. The few measurements we can make agree with this assumption.

For measuring time, we use the clock of General Relativity and what is known from astrophysical measurements. Before Creation began, time as we know it did not yet exist. Space did not yet exist either, and the Universe was just ‘nothing’.1 From this nothing therefore began the creation of space (the heavens of the Bible) and the emergence of the primitive matter in it.

Before moving on, however, I will mention that until the early twentieth century, the common scientific belief was that the Universe had no beginning. Space was believed to be eternal, as well as matter. It was not until after 1920 that it was discov- ered that the Universe indeed had a beginning.

Let us start with the Biblical description of the first day.2

In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. And the earth was formless and invisible and darkness covered the face of the deep. And the

This is equivalent to the μη ὄν in Greek.

New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright 1989, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. The number after the name of any Bible book gives the chapter.

Actor-Network Theory and Byzantine Philosophy

The text offers a detailed reflection on the results of almost 20 years of work focusing on the paradigm of Actor-Network-Theory (ANT), including the application of concepts and methods inherent in Byzantine philosophy. The motivation for such reflection is based on the opportunity to expand and systematize latest research insights on the same topic by Ivan Chalakov and Stoyan Tanev. The starting point is the attempt to unfold the sociological explanations of phenomena such as endurance, resistance and innovation, which are difficult to explain through the paradigms of classical sociology. The suggestedanalysis adopts concepts such as essence-power-energy, hexis, perichōrēsis, hypostasis, prosōpon andbody, to refine some of the positions characteristic of the ANT paradigm and propose new ones that allow to problematize the principle of symmetry, the understating of initiative, essence and the figure of the actor. The developed point of view is demonstrated by analyzing some of the paradoxes inherent in the understanding of the human hypostasis and the questions emerging from the theoretical prescriptions of transhumanism.

Introduction

Actor-Network-Theory (ANT) was articulated in the 1970s by Bruno Latour, Michel Callon, and their followers. It abandoned the ‘Cartesian’ subject-object scheme and challenged the existing sociological concepts of activity. Its emphasis is on the network interactivity between human and non-human beings. At the very beginning of the twenty-first century, Ivan Tchalakov and I initiated a research project focusing on exploring the ANT paradigm with a focus on social phenomena that were, in fact, unexplained by sociology at that time, such as endurance, persistence, resis- tance, and innovation. The key elements of our theoretical apparatus were based on the teachings and concepts of Byzantine philosophers. These concepts are: es- sence-power-energy, hexis, perichōrēsis, hypostasis, prosōpon, body. The results of our research problematized (by questioning the existing typology of social actions) the ANT concept of ‘translation’, which is used by ANT scholars as a replacement of the concept of ‘action’, and relativized the idea of ‘symmetry’, which is absolu- tized by the representatives of ANT. The application of the Byzantine conceptual apparatus opened new horizons, helped articulating new problems and challenges, opened new perspectives, as well as made it possible to refine and deepen the focus of the research project.

The Dialogue between Orthodox Theology and Science as Explication of the Human Condition

The paper discusses the philosophical sense of the dialogue between science and theology. It starts with the recognition that the foundation of both science and theology originates in human beings, having an ambiguous position in the universe that cannot be explicated on metaphysical grounds but can be interpreted theologically. The dialogue between science and theology demonstrates that the difference in hermeneutics of representation of the world in the phenomenality of objects and the inaugural events of human life and religious experience pertains to the basic characteristic of the human condition and that the intended overcoming of this difference under the guise of the ‘dialogue’ represents, in fact, an exis- tentially untenable enterprise. The paradoxical position of humanity in the world (being an object in the world and subject for the world) is treated as being the cause in the split between science and theology. Since, according to modern philosophy, no reconciliation between two opposites in the hermeneutics of the subject is possible, the whole issue of the facticity of human subjectivity as the sense-bestow- ing centre of being acquires theological dimensions, requiring new developments in both theology and philosophy. The intended overcoming of the unknowability of man by himself, tacitly attempted through the ‘reconciliation’ of science and theology (guided by a purpose to ground man in some metaphysical substance), is not ontologically achievable, but demonstrates the working of formal purposefulness (in the sense of Kant). Then the dialogue between theology and science can be considered a teleological activity representing an open-ended hermeneutics of the human condition.

Introduction

In any possible discussion of the relationship between theology and science (if theology is understood as experience of God through life and the physical sciences as explorations of the world within the already given life) there a question arises: What is the model that could best describe the relation between the experiential aspects of life and the knowledge of the world that positions humanity as one thing among others? In other words, if the Divine is perceived as the realm of the transcendent out of which life originates, whereas the operational realm of the physical sciences is related to the created world, the mediation between theology and science shouldde facto become an outward scientific explication of the meaning of the human condition in communion with the giver of life. This is a different perspective on the