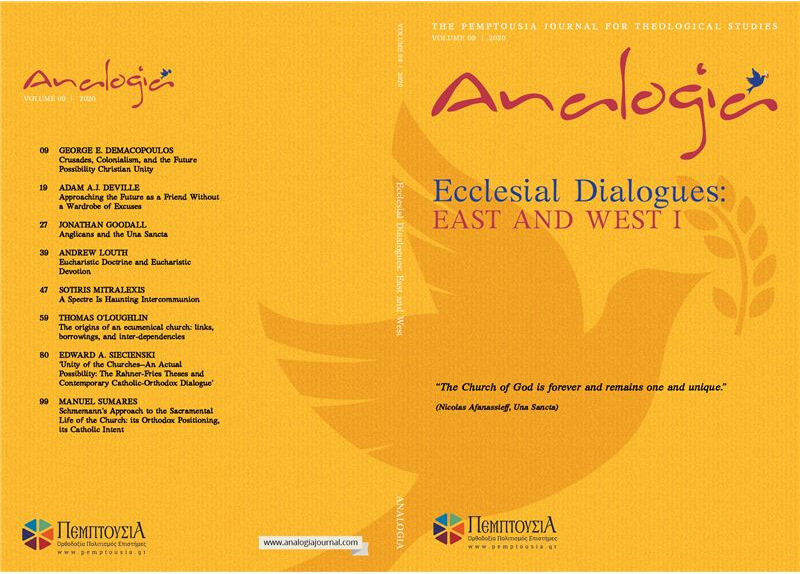

Volume 9 – Ecclesial Dialogues: East and West I

VIEW VOLUMEThe Church of God is forever and remains one and unique.

(Nicolas Afanassieff, Una Sancta)

Contents-Abstracts

Editorial

We are overjoyed that Analogia’s issues 9 and 10 are dedicated to Ecclesial Dialogues: East and West—that is, to peer-reviewed and revised versions of papers first presented at the international conference exploring this subject and convened in the island of Syros, from the 10th to the 14th of June 2019. This conference would not have materialised without the generous support of Loyola Marymount University’s Revd Professor Cyril Hovorun and the generous support of the University of Winchester (which provided the conference’s academic aegis) and our co-convenor, Revd Reader Andreas Andreopoulos; we extend our cordial gratitude to these individuals and institutions, as we remain with the hope that a particular vision (or rather, perspective) was articulated during those days in Syros, rather than merely yet another ecumenically-oriented scholarly gathering.

The guest editors deem it important that this conference (and the Analogia issues stemming therefrom) did not form part of any level of official ecclesial dialogue and exchange but consisted in a bottom-up scholarly endeavour at ecclesial enquiry, ex- ploration and discovery. The reader shall be spared the guest editors’ theological musings in this editorial note (yet these musings shall return vengefully in the guest editors’ respective papers). We have opted for one introduction to both issues, so that the interested reader will be made aware of the contents of the other issue, apart from the one you are currently holding in your hands.… Continue Reading

We are overjoyed that Analogia’s issues 9 and 10 are dedicated to Ecclesial Dialogues: East and West—that is, to peer-reviewed and revised versions of papers first presented at the international conference exploring this subject and convened in the island of Syros, from the 10th to the 14th of June 2019. This conference would not have materialised without the generous support of Loyola Marymount University’s Revd Professor Cyril Hovorun and the generous support of the University of Winchester (which provided the conference’s academic aegis) and our co-convenor, Revd Reader Andreas Andreopoulos; we extend our cordial gratitude to these individuals and institutions, as we remain with the hope that a particular vision (or rather, perspective) was articulated during those days in Syros, rather than merely yet another ecumenically-oriented scholarly gathering.

The guest editors deem it important that this conference (and the Analogia issues stemming therefrom) did not form part of any level of official ecclesial dialogue and exchange but consisted in a bottom-up scholarly endeavour at ecclesial enquiry, ex- ploration and discovery. The reader shall be spared the guest editors’ theological musings in this editorial note (yet these musings shall return vengefully in the guest editors’ respective papers). We have opted for one introduction to both issues, so that the interested reader will be made aware of the contents of the other issue, apart from the one you are currently holding in your hands.

Ecclesial Dialogues: East and West I (i.e., Analogia 9) opens with Dr Sotiris Mitralexis’ (Orthodox, University of Winchester & University of Athens) ‘A Spectre Is Haunting Intercommunion’, an introduction to the conference’s problematic. Professor Edward Siecienski’s (Orthodox, Stockton University) paper follows, entitled ‘Unity of the Churches—An Actual Possibility: The Rahner-Fries Theses and Contemporary Catholic-Orthodox Dialogue’, highlighting from a contemporary perspective the eight theses that Karl Rahner, SJ and Heinrich Fries proposed in 1983, in the hope of healing Christianity’s many divisions. Revd Professor Thomas O’Loughlin (Catholic, University of Nottingham) then proceeds in his ‘The Origins of an Ecumenical Church: Links, Borrowings, and Inter-dependencies’ to examine the ecclesiology of early churches as nodes within a network, established and maintained by constant contact and by those who saw it as part of their service/vocation to travel between the churches; this culture of links, of sharing and borrowing, could perhaps form a model for a practical way forward today towards a renewed sense of our oneness in Christ. In ‘Crusades, Colonialism, and the Future Possibility of Christian Unity’, Professor George Demacopoulos (Orthodox, Fordham University) presents the historical conditions more extensively laid out in his recent monograph Colonizing Christianity: Greek and Latin Religious Identity in the Era of the Fourth Crusade (New York: Fordham University Press, 2019) in order to develop a more constructive theological argument regarding the ecumenical implications of that historical work. Revd Professor Andrew Louth (Orthodox, Durham University) focuses in his ‘Eucharistic Doctrine and Eucharistic Devotion’ on comparing the Western Rite of Benediction, Exposition of the Host and adoration, with the Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts in the East; the nature of Eucharistic devotion expressed in these two rites is in most ways strikingly different, and this leads Revd Professor Louth to highlight differences that are rather rarely discussed in ecumenical discussions. Revd Dr Manuel Gonçalves Sumares (Orthodox, Catholic University of Portugal, Braga) centres on the late Fr Alexander Schmemann (and Sergius Bulgakov, among many others) in his ‘Schmemann’s Approach to the Sacramental Life of the Church: its Orthodox Positioning, its Catholic Intent’. Revd Professor Adam AJ DeVille (Catholic, University of Saint Francis) offers an Eastern Catholic perspective in his ‘Approaching the Future as a Friend Without a Wardrobe of Excuses’, including moral questions around marriage and divorce, historiographical and liturgical-hagiographical questions centred on the canonization and commemoration of saints in one communion who left and/or were used in conciliar debates and liturgical texts to condemn the sister communion; and questions of synodal organization and structures in both Catholicism and Orthodoxy in the face of centralizing tendencies. The first issue concludes with a rich Anglican perspective presented by the Rt Revd Jonathan Goodall, Bishop of Ebbsfleet and Archbishop of Canterbury’s Representative to the Orthodox Church: in his ‘Anglicans and the Una Sancta’, Bishop Jonathan stresses the Anglican self-understanding as ‘part of the One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church’.

Ecclesial Dialogues: East and West II (i.e., Analogia 10) starts with the Senior Editor of Analogia, Revd Professor Nicholas Loudovikos (Orthodox, University Ecclesiastical Academy of Thessaloniki, University of Winchester, IOCS Cambridge, Orthodox Secretary of the ‘St Irenaeus’ Joint Catholic-Orthodox International Working Group) and his paper on ‘Christological or Analogical Primacy: Ecclesial Unity and Universal Primacy in the Orthodox Church’, according to which ‘the only way Christ makes himself analogically present as the head of his Church, through a universal Primate, is as manifestation of a consubstantializing Synodality’. Professor Andrew TJ Kaethler (Catholic, Catholic Pacific College), in his ‘Manifesting Persons: A Church in Tension’, begins from a theological notion of personhood in order to provide a broad framework or an imaginative construct to conceive of Church unity, in light of Joseph Ratzinger’s and Romano Guardini’s respective theologies. Kaethler suggests that the East and West will, perhaps, most flourish in a united tension, a coming together of difference rather than a complete dissolving of our respective distinctions. Following this, Professor Jared Schumacher (Catholic, University of Mary) formulates ‘An Ignatian-MacIntyrean Proposal for Overcoming Historical and Political-Theological Difficulties in Ecumenical Dialogue’, focusing on three difficulties in achieving practical unity: the recognition of plurality, the problem of synthesis or integration, and the problem of orientation implicit in any synthesis.

Returning ad fontes, Professor Christos Karakolis (Orthodox, University of Athens) examines the character of Simon Peter in the narrative of John’s Gospel in his ‘Simon Peter in the Gospel According to John: His Historical Significance according to the Johannine Community’s Narrative’, in order to help us better understand the biblical foundations of the theological debate on the papal office. Fast-forward to the 6th century with Professor Anna Zhyrkova’s (Catholic, Akademia Ignatianum, Krakow) ‘The Scythian Monks’ Latin-cum-Eastern Approach to Tradition: A Paradigm for Reunifying Doctrines and Overcoming Schism’, which presents the historical case study of the Scythian monks, who united Western and Eastern traditions, seeing both traditions as one and not hesitating to address problems simultaneously of concern to both Rome and Constantinople, putting forward a solution based on a synthesis of Augustine’s and Cyril’s theologies. Escaping doctrinal differences per se and turning our attention to aesthetics —a perspective rarely addressed in East-West dialogues—, Professor Norm Klassen (Catholic, University of Waterloo) offers in his ‘Beauty is the Church’s Unity: Supernatural Finality, Aesthetics, and Catholic–Orthodox Dialogue’ an understanding of beauty vis-à-vis the nature/ grace question, inter alia via a reference to Rowan Williams’ thought. The con- ference’s co-convener Revd Reader Andreas Andreopoulos (Orthodox, University of Winchester) proposes in his ‘Ecumenism and Trust: A Pope on Mount Athos’ a hypothetical scenario, an exercise in imagination, an ecumenical Christian-fi in the manner of sci-fi, according to which a particularly humble Pope of Rome visits Mount Athos, the bastion of Orthodox asceticism, in search of unity and in an ecclesial version of the famous 1971-72 dictum ‘only Nixon could go to China’; the point is that it is necessary to recognize the multitude of levels and dimensions of dialogue and the question of the reunification of the East and the West, well beyond the remit of joint theological commissions, and that establishment of mutual trust among clergy, monastics and laity on both sides is the first necessary step. Remaining on Mount Athos and its attempted Catholic equivalent, Dr Marcin Podbielski (Catholic, Akademia Ignatianum, Krakow) shares in his philosophically-informed ‘God’s Silence and Its Icons: A Catholic’s Experiences at Mount Athos and Mount Jamna’ his ‘bewilderment [that] there seems to be almost no room in contemporary Catholic spirituality for silence and isolation’ and presents Athos and Jamna as two different realizations of an icon given to us by Christ himself, as human instruments which we create to point to true participation in the Divine presence of the New Jerusalem. Whereas the Catholic experience tries to bring everyone into participation in the life of the New Jerusalem, the Orthodox Athos, in its silent uniqueness, testifies to a unique and ineffable transcendence. Returning to more mainstream themes in East-West dialogue, Revd Dr Johannes Börjesson (University of Cambridge) offers in his ‘Councils and Canons’ a Lutheran perspective on the Great Schism and the ‘Eighth Council’ via Lutheran ecclesiology. From a ‘Radical Orthodox’ perspective within Anglicanism and beyond, Professor John Milbank (University of Nottingham) argues in his ‘Ecumenism done otherwise: Christian unity and global crisis’ for a connection of ecumenism to politics, and suggests that any relevant dialogue should theologically assume that Church unity already exists but has been obscured and obfuscated—with our task being to recover and disclose this unity. Completing our Analogia issues, Professor Marcello La Matina (Catholic, University of Macerata) offers the closing thoughts of this collective endeavour from the perspective of a scholar of the philosophy of language in his paper ‘Concluding Reflections on Mapping the Una Sancta: An Orthodox-Catholic Ecclesiology Today’, proposing an understanding of the schism as the stage of the mirror, as Jacques Lacan would have it.

In closing this editorial note, we would like to thank the following institutions and sponsors: again, Loyola Marymount University and the University of Winchester, for making the conference possible; Catholic Pacific College and the Municipality of Syros for their support, as well as His Excellency J. Michael Miller, CSB, the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Vancouver. We are filially grateful to His All- Holiness Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew, His Beatitude Ieronymos II, Orthodox Archbishop of Athens and All Greece, to His Eminence Dorotheos, Orthodox Metropolitan of Syros, Tinos, Andros, Kea and Milos, and to His Excellency Petros Stephanou, Catholic Bishop of Syros, Milos, Santorini and Apostolic administrator of the Diocese of Crete, for their kind permission and blessing of the conference. Revd Professor Nikolaos Loudovikos has kindly proposed the publication of the Syros papers in Analogia following successful peer-review; we are most thankful to him for this invitation. We remain with the hope that this collective endeavour forms the beginning, rather than the completion, of an attempt at seeing ecclesial dialogues between East and West from a particular and hopefully fresh perspective.

– Dr Sotiris Mitralexis & Dr Andrew Kaethler, Guest Editors

Schmemann’s Approach To The Sacramental Life Of The Church: Its Orthodox Positioning, Its Catholic Intent

[…] we need in this world the experience of the other world, its beauty, depth, treasure, the experience of the Kingdom of God and its Sacrament – the Eucharist.

Alexander Schmemann, The Journals, p. 24–25.

The nominalist contagion has become transversal in contemporary culture. Schmemann sees it as pervasive in Western Christianity, but it can be also found in the Eastern Church in the excessive ritualism and formalism associated with Byzantium: in sum, Orthodoxism and the issue of clericalism. Moreover, the transversality of nominalism is such that it practically defines secularism with its own universalist pretensions. The two great church bodies that see themselves as apostolic and catholic would do well to look back to Schmemann’s criteria for the right kind of consolidations, especially in regard to sacramental realism, to break the hold of nominalism. In exploring this theme, we shall note Paul Ricoeur’s critical hermeneutics to bring forth the peculiarities of Schmemann’s Orthodox positioning, and, we shall briefly allude to some facets of Donald Davidson’s theory of radical interpretation to suggest how the dialogue might proceed, as well as Bulgakov’s own take on Una Sancta and where it meets one of Schmemann’s crucial concerns.

1

The issue of ‘Mapping the Una Sancta’ would have interested Father Alexander Schmemann. To begin with, from the time of his upbringing in Paris to his mission on behalf of the Orthodox Church in North America, his relationship with the Roman Catholic Church was been never less than meaningful.1 Along with his

In his Journals he would recall his student life in Paris and the positive experience of stopping by to hear parts of the Catholic Mass. He associated with it the same intuition that he experienced as an Orthodox and will have a place in this essay, namely, ‘the coexistence of two heterogeneous worlds, the presence in this world of something absolutely and totally “other.” This “other” illumines everything, in one way or another. Everything is related to it—the Church as the Kingdom of God among and inside us.’ The Journals of Father Alexander Schmemann (1973–1983) translated by Juliana Schmemann (Crestwood: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2000), 19. Besides his interest in the works of Catholic theologians, specifically those associated with La nouvelle théologie and the idea of returning to the Fathers as an important resource for overcoming the dominance of neo-scholastic theology in their Church, he became an Orthodox observer at the Second Vatican Council. From the Catholic side, Fr Richard John Neuhaus’s admirable and admiring recollection of him in, ‘A Man in Full’, written on the occasion of Schmemann’s posthumous publication of his Journals in the influential periodical, First Things (January, 2001), gives us a picture of a man to be reckoned with.

‘Unity of the Churches—An Actual Possibility: The Rahner-Fries Theses and Contemporary Catholic-Orthodox Dialogue’

In 1983 Karl Rahner, SJ and Heinrich Fries wrote Unity of the Churches: An Actual Possibility (Einigung der Kirchen—reale Möglichkeit) a small book proposing eight theses that they hoped could bring about the almost immediate reunion of Christendom. Although widely criticized for their ‘epistemological tolerance’, if ‘resurrected’ and properly adapted to issues currently under discussion in the Catholic-Orthodox dialogue (e.g., the filioque, the papacy, the Marian dogmas), these theses (particularly 1, 2, 4a, 4b) have the potential to build upon the progress already made and move East and West even closer toward full communion.

A Personal Note

In the years since the publication of my book on the filioque,1 and then its companion volume on the papacy,2 I have been asked many times by both Catholic and Orthodox friends if and when these debates will end so that the goal of unity between the churches can finally become a reality. Up to this point I have not addressed these questions in print, because until now I have restricted myself to chronicling what has been rather than detailing what should be. My work has largely been descriptive rather than prescriptive, a natural consequence of being a dogmatic historian far more concerned with the past rather than with the future.

However, I must admit that as a scholar who has spent the last two decades studying the genesis and progression of the schism I have often wanted to take the

A. Edward Siecienski, The Filioque: History of a Doctrinal Controversy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010).

A. Edward Siecienski, The Papacy and the Orthodox: Sources and History of a Debate (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017).

The origins of an ecumenical church: links, borrowings, and inter-dependencies

The creed’s confession that we believe in ‘one holy catholic church’ should not simply be understood as a doctrinal datum, but as an understanding of the Spirit’s work based in the experience of the early churches. The churches did not exist as discrete groups with merely a common religious profession, but as nodes within a network. This network was established and maintained by constant contact and by those who saw it as part of their service/vocation to travel between the churches—and these human and physical links account for how the Christian Church as a whole developed; its common heritage in the writings it produced which became, in time, the canonical collection; and its awareness that, despite difficulties, such links were essential to its identity. This culture of links, of sharing and borrowing, could form a model for a practical way forward today towards a renewed sense of our oneness in the Christ.

Around 150 CE we get the first explicit mention of the one Church—encompassing all the communities of Christians—as itself an intrinsic element of the Christian faith. The statement comes from the Epistula apostolorum and takes this creedal form:

Then when we had no food except five loaves and two fish, he commanded the men to recline. And their number was found to be five thousand besides women and children, and to these we brought pieces of bread. And they were satisfied and there was some left over, and we removed twelve baskets full of pieces. If we ask and say, ‘what do these five loaves mean?’, they are an image of our faith as true Christians; that is, in the Father, ruler of the world, and in Jesus Christ, and in the Holy Spirit, and in the holy church, and in the forgiveness of sins. (5,17–21).1

This text, the Epistula, presents historians with a wonderful array of problems such as how it relates to those texts, the gospels, which were at that time shifting in their status from being the standard and, possibly somehow authoritative, texts in use in the churches towards becoming the canonical texts of those groups by

I rely on Francis Watson, An Apostolic Gospel: The Epistula Apostolorum in Literary Context (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, forthcoming) for the dating and the translation of the Epistula. I am indebted to Prof. Watson for making available to me his work, ahead of publication, so that I could cite it here.

A Spectre Is Haunting Intercommunion

As an introduction to the current issue, this paper looks at certain details of the current state of the ecclesial dialogue between East and West, in light of Edward Siecienski’s two important contributions, The Papacy and the Orthodox: Sources and History of a Debate (Oxford University Press, 2017) and The Filioque: History of a Doctrinal Controversy (Oxford University Press, 2010) and of other sources. The core question of the paper is, which Church is the “One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church” that we confess to during each liturgy and mass? Is it one of two divided Churches, or the one Church in schism?

1

Allow me to start with my personal incentives for embarking upon this enquiry. Reading Edward Siecienski’s treatises on the history of the divide, the recent The Papacy and the Orthodox: Sources and History of a Debate1 and his earlier The Filioque: History of a Doctrinal Controversy,2 I saw with considerable clarity that the actual historical trajectories of the Orthodox and the Catholic Church, in all the vertiginous complexity of these trajectories in all their details, look quite different from the simplified, retroactively formulated historical narratives concerning purported clear-cut divisions.

Of course, there is much to be said about which differences are indeed seemingly or currently irreconcilable doctrinal and ecclesiological divisions and which differences are merely legitimate local liturgical, ecclesiological and theological traditions, from the vast pool of theologoumena, of apostolic churches comprised of different peoples and at different points and circumstances in history. It must be remarked that this diversity of legitimate traditions of apostolic churches has also been largely lost within both the Roman and the Byzantine Church, in view of the homogenisation that emerged during the reign of the empires within which each of these churches flourished.

A. Edward Siecienski, The Papacy and the Orthodox: Sources and History of a Debate (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017).

A. Edward Siecienski, The Filioque: History of a Doctrinal Controversy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010).

Eucharistic Doctrine and Eucharistic Devotion

Although there are doubtless some (mostly Orthodox) who would disagree, it seems safe to say that, so far as the doctrine of the Eucharist is concerned, there is agreement between both Orthodox and Catholic: that is, we both affirm that that in the Eucharist Christ becomes present, in his full humanity and full divinity, as the Body and Blood of Christ, the elements of bread and wine having been changed by the Eucharistic prayer. Furthermore, this presence is not fleeting; the Holy Gifts are reserved and given as the Body and Blood of Christ. In addition, both Orthodox and Catholic are agreed on the sacrificial nature of the Eucharist. But what about devotion to Christ present in the Eucharist? More specifically, what about devotion to Christ’s consecrated Body and Blood outside the Eucharist, which in the West is called ‘extra-liturgical’ devotion? There is a sense in which there is no extra-liturgical devotion to the consecrated Holy Gifts among the Orthodox; the sacrament is reserved in an artophorion kept on the holy table, but it receives no especial devotion separate from the Holy Table itself. This paper will concentrate on comparing the Western Rite of Benediction and, closely associated with this, the Exposition of the Host and Adoration, with the Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts in the East. Despite accord on doctrine, the nature of Eucharistic devotion expressed in these two rites is in most ways strikingly different.

I think I have taken the subject of our colloquy, Mapping the Una Sancta, in perhaps a slightly different way from most of us here. I understood Dr Sotiris Mitralexis’s suggestion, when he asked me to take place in the Syros Symposium, to be that we think ahead and begin to consider what the next steps might be if Catholics and Orthodox reached the conviction that there are no doctrinal differences between us. Judging from the abstracts, several have taken this to mean the papacy, looking at the last major issue—which is why Edward Siecienski’s book on the papacy has been suggested as preliminary reading—and wondering if we are approaching this issue in the right way. I took Sotiris’s suggestion in a different way: if we were agreed on doctrinal issues, are there other issues that might distinguish or even divide us? Issues where, although there is no real doctrinal disagreement, there are still differences of ethos or of devotion: what might these differences entail? My proposal is to consider this in relation to the Eucharist, for although there are doubtless some (mostly Orthodox) who would disagree, it seems safe to say that, so far as the doctrine of the Eucharist is concerned, there is broad agreement between Orthodox and Catholic: that is, we both affirm that that in the Eucharist Christ becomes present, in his full humanity and full divinity, as the Body and Blood of Christ, into

Anglicans and the Una Sancta

The Church of England, which in origin is two separated provinces of the Western Latin Church, became formative of the Anglican Communion worldwide. However, it has never in those years of separation considered itself wholly separated in the sense that it has always asserted its connectedness and incompleteness as ‘part of the one holy catholic and apostolic Church’, independent in polity, interdependent with other Anglicans and other churches, especially those ordered in the historic episcopate. More recently, asserting its legitimate patrimony, it has sought ecclesial unity without simply being absorbed into the polity of those with a more exclusive claim to identity with the Una Sancta, causing Anglicans to wrestle with the legitimate terms of communion in the Una Sancta. This journey has been at its most complex and rewarding with the Roman Catholic Church, especially in relation to the terms of communion focused on the papal office.

‘Those who do not smart from the wounds of Christ’s body are not nourished by the Spirit of Christ’

Non vegetate Spiritu Christi

qui non sentit vulnerabilis corporis Christi

Peter the Venerable, Abbot of Cluny

A part not the whole

‘The Church of England is part of the One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church, worshipping the one true God, Father, Son and Holy Spirit.’ Thus begins the preface to the Declaration of Assent, approved through a process involving the Lambeth Conference of 1968, which all deacons, priests, and bishops in the Church of England have for nearly fifty years had to affirm publicly at their oath-taking either when they are ordained and on every new appointment. It is increasingly used in ecumenical discussion as the definition of the Church of England’s position. For example, in the English bishops’ response to the papal encyclical Ut unum sint, it was quoted in relation to the use of the verb ‘subsistere in’ at the Second Vatican Council: not only in Lumen gentium (to affirm that all the elements of sanctification and truth can be found in the Catholic Church), but also in Unitatis redintegratio to say

Approaching the Future as a Friend Without a Wardrobe of Excuses

This paper touches on some issues having virtually no place in official Catholic-Orthodox dialogue, including moral questions around marriage and divorce; historiographical and liturgical-hagiographical questions centred on the canonization and commemoration of saints in one communion who left and/or were used in conciliar debates and liturgical texts to condemn the sister communion; and questions of synodal organization and structures in both Catholicism and Orthodoxy in the face of centralizing tendencies. It proposes a model of ‘gradual’ and localized sacramental communion inspired in part by the work of several contemporary Orthodox scholars—Staniloae, Bordeianu, Plekon, Arjakovsky, inter alia.

Introduction

I began my official involvement with the ecumenical movement in high-school in 1988, assisting a local chapter of the Anglican-Roman Catholic dialogue in south- western Ontario. Then, in 1990, I became involved with the Canadian Council of Churches and the World Council of Churches whose seventh assembly in Canberra, Australia I attended, followed by seven years of working for the WCC during which I crossed the globe to many gatherings on five continents.

I learned immediately after returning from Australia in 1991 that the over- whelming majority of Christians had never even heard of the WCC, and had little clue as to what the word ‘ecumenism’ or its cognates even meant, and, more alarming still, they seemed completely uninterested in learning more. Worse still, those tiny few who actually were aware of the WCC were almost uniformly hostile, picketing our worship tent in Australia every morning with Pauline proof-texts (‘be ye not yoked together with unbelievers!’) or later taking to the pages of that august and venerable journal of theological scholarship, Reader’s Digest, to denounce the WCC as a vehicle for advancing what a contemporary Canadian crank, fondly imagining he has invented the phrase, calls ‘cultural Marxism’.

While depressing, this realization that the vast majority of people knew little and cared even less about ecumenism was sobering and helpful when we would get

My title is a paraphrase of a line from W.H. Auden’s 1940 poem ‘In Memory of Sigmund Freud’.

Crusades, Colonialism, and the Future Possibility Christian Unity

Why does interpreting the Fourth Crusade as a colonial encounter usefully recalibrate our understanding of the rapid escalation of Orthodox/Catholic animus that occurred during the thirteenth century and what are the ecumenical implications of this reorientation? Scholars have long since identified the Fourth Crusade as a pivotal moment in the history of Orthodox/Catholic estrangement so, why, one might ask, do we need to view the crusades as colonialism per se in order to chart the history of Orthodox/Catholic estrangement? And why do we need the theoretical resources of postcolonial critique to explain something we already know?

In a recent book, Colonizing Christianity: Greek and Latin Religious Identity in the Era of the Fourth Crusade (Fordham, 2019), I argued that the religious polemics, both Greek and Latin, that emerged in the context of the Fourth Crusade should be interpreted as having been produced in a colonial setting and, as such, reveal the political, economic, and cultural uncertainty of communities in conflict; they do not offer theological insight.1 Given that it was in the context of the Fourth Crusade—and not the so-called Photian Schism of the ninth century, the so-called Great Schism of 1054, or any other period of ecclesiastical controversy—that Greek and Latin apologists developed the most elaborate condemnations of one another, I argued, it behooves historians, theologians, and Church leaders alike to reconsider the conditions that give rise to the most deliberate efforts to forbid Greek and Latin sacramental unity in the Middle Ages and to ask whether those arguments are theologically revealing or whether they simply convey animosity in the guise of theological disputation. This essay begins with a summary of these historical conditions and then develops a more constructive theological argument regarding the ecumenical implications of that historical work.

I began the book by asking the reader to consider with me how treating the Fourth Crusade as a colonial encounter might alter our interpretation of Orthodox/ Catholic hostility, which first took its mature form in that context. Four of the

George Demacopoulos, Colonizing Christianity: Greek and Latin Religious Identity in the Era of the Fourth Crusade (New York: Fordham University Press, 2019).