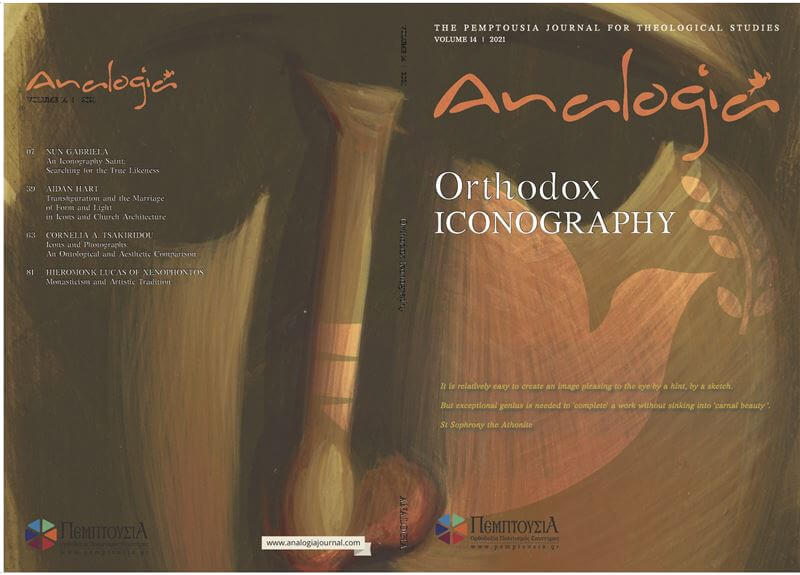

Volume 14 – Orthodox Iconography

It is relatively easy to create an image pleasing to the eye by a hint, by a sketch. But exceptional genius is needed to ‘complete’ a work without sinking into ‘carnal beauty ‘.

(St Sophrony the Athonite)

Contents-Abstracts

Editorial

This is the first of a three-volume series dedicated to Orthodox Iconography. In the life of the Church, Iconography, as theology through colours, has been, in the life of the Church, more than anything else, the expression of ineffable things, that is, things that cannot be expressed through words and concepts. For Orthodox theology, the experience of vision that surpasses reason and conceptualisation has always been the way par excellence of approaching divine things, not in the sense that we understand them, since they lie beyond understanding, but in the sense that we participate in them. The vision of God, beyond any philosophical/intellectual contemplation, formed the core of a great part of the Greek Patristic ascetical literature. Of course, this vision is also ineffable and non-depictable, but, however, Iconography is still what lies closer to this experience, and it directly refers to the latter. Iconography, in that sense, does not mean so much that one thinks though icons, but mainly that one prays through icons.

So, the first author of this volume, Nun Gabriela, claims, referring to the iconographic legacy of St Sophrony the Athonite, who was her spiritual guide and iconography teacher, claims that for him, to paint icons means to ‘express one’s vision and knowledge of Christ’. That is, an icon’s purpose is ‘to inspire prayer and be a link to the person depicted’. According to St Sophrony, iconographic inspiration has to be tested through prayer; and that means that it has to be a part of a process of spiritual maturation in the Holy Spirit. Iconography, or perhaps better, hagiography, as is the Greek term, portrays this process in the Church σύν πᾶσι τοῖς ἁγίοις, that is, together with all the saints. This is why Sophrony‘s method was ‘to paint only the essentials and concentrate on the face which is the mirror of the soul’. Beyond the technical details, which of course are invaluable, St Sophrony’s artistic activity was precisely a theology of the ineffable, a sign of divine participation.… Continue Reading

This is the first of a three-volume series dedicated to Orthodox Iconography. In the life of the Church, Iconography, as theology through colours, has been, in the life of the Church, more than anything else, the expression of ineffable things, that is, things that cannot be expressed through words and concepts. For Orthodox theology, the experience of vision that surpasses reason and conceptualisation has always been the way par excellence of approaching divine things, not in the sense that we understand them, since they lie beyond understanding, but in the sense that we participate in them. The vision of God, beyond any philosophical/intellectual contemplation, formed the core of a great part of the Greek Patristic ascetical literature. Of course, this vision is also ineffable and non-depictable, but, however, Iconography is still what lies closer to this experience, and it directly refers to the latter. Iconography, in that sense, does not mean so much that one thinks though icons, but mainly that one prays through icons.

So, the first author of this volume, Nun Gabriela, claims, referring to the iconographic legacy of St Sophrony the Athonite, who was her spiritual guide and iconography teacher, claims that for him, to paint icons means to ‘express one’s vision and knowledge of Christ’. That is, an icon’s purpose is ‘to inspire prayer and be a link to the person depicted’. According to St Sophrony, iconographic inspiration has to be tested through prayer; and that means that it has to be a part of a process of spiritual maturation in the Holy Spirit. Iconography, or perhaps better, hagiography, as is the Greek term, portrays this process in the Church σύν πᾶσι τοῖς ἁγίοις, that is, together with all the saints. This is why Sophrony‘s method was ‘to paint only the essentials and concentrate on the face which is the mirror of the soul’. Beyond the technical details, which of course are invaluable, St Sophrony’s artistic activity was precisely a theology of the ineffable, a sign of divine participation.

Aidan Hart’s guiding question is: ‘people will worship within the Church that I am designing, so how can I help create a state of soul most receptive to divine grace, create an atmosphere conducive to compunction, awe, and peace?’ This leads him to search for a precious theology of light in Orthodox temples, something which in turn leads him to realise that ‘transfiguration is not dematerialisation. Light (symbolic of divine Grace), unites with matter (symbolic of the whole created world), in a union without confusion, so that both continue their existence’.

Prof. Cornelia Tsakiridou invents the term intermediality in order to describe the possible convergence-in-distinction between icons and photographs in a theological perspective. For her, ‘intermediality is a perichoretic state that implies, as the term perichoresis suggests, a coinhering relationship between artistic genres, in which their similarities and differences are affirmed, articulated, and recalibrated. Intermediality also means that we can think about photographs and icons in new ways. For example, we can see photographs as perceptual and mnemonic fields, where things deposit their impressions and subsist in a literal and representational eternity, detached and yet fully immersed in the world from which they were extricated. And we can look at icons as frames that configure a noetic or pneumatic space where beings linger free from the constraints of physical existence, without, however, relinquishing their physicality. Rather than dissolve matter, photographs and icons carry it over to another dimension and themselves exist in that order, fusing phenomenal and ontic realities.’

For fr Lukas, finally, what is essential is a loving and creative approach to the icon through the spiritual life on Mount Athos. For him ‘the true artist is not the one who reproduces prototypes, but rather he who prophetically foresees and directs his inspirations to the desires and expectations of the community of the Church’.

I am grateful for the brilliant contributions of this volume. Nun Gabriela, Aidan Hart, and fr Lukas, are also practicing iconographers, and give us some excellent samples of their work. The purpose of this three-volume series is to present some of the most important representatives of contemporary Orthodox Iconography, their work and their ideas, along with some of the most important thinkers on Orthodox Art and Theology of Icons. I am grateful to Dr Georgios Kordis, a world-renowned Iconographer and academic teacher of Iconography, who very kindly supported this series in many ways. Professor Tsakiridou is also one of the people behind the creation of this series, to whom many thanks are due.

– Nikolaos Loudovikos, Senior Editor

Monasticism and Artistic Tradition

Holy Athos, the Holy Mountain, is a place where nobody is born. It is perhaps because of this that the spiritual rebirth of many people who wish to go together with the God-man Jesus Christ in his sacrificial course takes place there: a course where the risk, the escape presented by the confidence of an easy life, is at the same time an opening to beauty. This is where iconography flourished and tradition is preserved and continuously recreated.

It is perhaps because of this that the monasteries are interwoven with the beauty, with the ‘filokaliki’ or artistic attempt to experience deification. It is not by chance that the monasteries are where all the arts have flourished, more than in any other place. It is here the entire ancient and later patristic scriptures that were about to be annihilated by wear were copied. But they did much more than merely copy; they embellished them with their famous miniatures, which propelled the scriptures into visual marvel.

Here the chants were perfected and preserved, here the rituals of the services remained unaltered over the course of time, echoing the life eternal and implying the unspoken glory of the heavenly hierarchy. Here, finally, we will meet the unparalleled teachers and masters of byzantine iconography. The great Manuel Panselinos in the renowned temple of Protato in Carries mysteriously left behind his presence. Here Theophanis the Kris, the monk and hagiographer, under the heavy veil of Turkish occupation, rescues and entertains the Greek genus. Here a crowd of anonymous and eponymous humble deacons of byzantine iconography mixed—along with the pigments—their heart and their desire for the glory of God. In such a manner, the Panagia Portaitissa worked wonders and healed the daughter of the Tsar of Russia through the copy of her icon.

An iconographer Saint; Searching for the True Likeness

St Sophrony (Sakharov), recently included in the catalogue of saints,1 is best known for his theological writings. However, during the first years of his adult life, he dedicated himself to a career as a painter. Unable to find fulfillment in this profession, he left the world for Mt Athos at the age of 29. He spent the next sixty-year period as a monk, a hermit, a priest, and a spiritual father. He founded a monastery and wrote several books about his elder, St Silouan, and about his own experiences, mainly as a hesychast. In his later years during the building of his monastery, of necessity, he returned to painting, more particularly to iconography, and expressed his spiritual wisdom with colour and brushes.2

St Sophrony’s journey to the icon

‘The act of the creation of all things is a mystery drawing us to Him.’3

St Sophrony’s early life was dedicated to painting. Through his art he tried to fathom and solve the questions that tormented him about life, about Being, about death and eternity. While this brought him through the path of abstraction, he ultimately realised that the solution to all his quests was the Creator of the universe not the creation. During ardent prayer of repentance for having arrogantly turned away from his childhood beliefs in search of something he deemed higher and loftier, Christ came to him.

St Sophrony was added to the list of saints by the Ecumenical Patriarch in November of 2019.

Due to failing eyesight and physical strength, toward the end of his life, St Sophrony was unable to paint and climbed the scaffolding for the last time at the age of ninety to touch up a work.

A. Sophrony, We Shall See Him, (Stavropegic Monastery of St John the Baptist, 1988), 150.

Icons and Photographs: An Ontological and Aesthetic Comparison

This paper explores ontological and aesthetic similarities and differences between icons and photographs and the tensions that characterize them. It looks at photography’s auxiliary role in Athonite iconography, its influence on the depiction of contemporary saints, and its use in the reproduction of icons for public consumption. The comparison shows that photography has the plastic and expressive capacity to engage spiritual realities.

The notion that in its quest for immutable realities the mind replaces sensuous with noetic forms originates in Plato’s metaphysics. Whether in nature or in art, sensible things are seen as fragmented and disjointed, like the conflicting perspectives they elicit in their viewers, and in need of organization from a higher conceptual level. Thus, as the mind leaves the physical world behind, it substitutes simplicity for plurality, clarity for opacity, and integration for dispersion. This form of idealism was embraced by Orthodox theology when it cast images as theological primitives that are good for the illiterate or serve as prompts for devotion and contemplative prayer, but not much else.

The idealist construction of art is problematic because it is too restrictive. We can see this in Hegel’s aesthetics where, as in Plato, images are incrementally subordinated to concepts.2 The logic is simple and appealing. Even though it is the originary form of transcendental reflection, art is too sensuous to host speculative categories once these become clear for the mind.

For Father Andrew Louth.

C.A. Tsakiridou, ‘Art’s Self-Disclosure: Hegelian Insights into Cinematic and Modernist Space’, Evental Aesthetics 1, n. 1 (2013). 45–72. Idem, ‘Darstellung: Reflections on Art, Logic and System in Hegel,’ The Owl of Minerva 23, issue 1 (Fall 1991), 15–28.

Transfiguration and the Marriage of Form and Light in Icons and Church Architecture

his article explores the relationship of light and matter in traditional icon painting and church architecture. In particular, it considers how this use of light reflects the Orthodox Church’s theology of deification, the material world’s transfiguration, the presence of divine logoi within the created world, and the capacity of aesthetics to help nurture the state of soul required for theosis. We might call this the ascetics of sacred aesthetics.

In this article we will discuss how the transfiguration of the created world in Christ finds expression in the formal or stylistic means of liturgical art, such as for example the way icons are highlighted, the translucency of the paint, the choice of colour, and the way Byzantine architects managed light and shade in their churches.

The invisible God cannot of himself be depicted. We depict God become flesh. However, the fact of divine grace working within the saints and the material world can be hinted at in the expressive forms of litur- gical art. Grace manifests itself through the people and things within which it acts. This objectively changes both the subjects it acts upon and the way we see them. The liturgical texts of the Transfiguration feast allude to both these transformations. Christ himself was transfigured: ‘You were transfigured on the mountain, O Christ God, revealing Your glory to Your disciples as far as they could bear it’.2 But at the same time the eyes of the disciples were transfigured so that they could see Christ as he always was: ‘Enlightening the disciples that were with Thee, O Christ our Benefactor, Thou hast shown them upon the holy mountain the hidden and blinding light of Thy nature and of Thy divine beauty beneath the flesh’.3 To deny the capacity of art to indicate this transfiguration is to deny the capacity of the material world and the human body to participate in divine grace in any meaningful way.

All photos included in this article are by author, except fig. 10

From the Troparion of the feast. The Festal Menaion, trans. Mother Mary and Archiman- drite Kallistos Ware (London: Faber and Faber), 477.

From Matins, Sessional Hymn. The Festal Menaion, 479.