Volume 1 – Mary, The Theotokos

VIEW VOLUMEMy soul doth magnify the Lord, and my spririt hath rejoiced in God my Saviour. For he hath regarded the low estate of his handmaiden: for, behold, from henceforth all genertions shall call me blessed. For he that is mighty hath done to me great things; and holy is his name. And mercy is on them that fear him from generation to generation.

Contents-Abstracts

Editorial

What is it that we call theology?

On an epistemological level, there is no doubt that the response seems easy: theology is every discourse concerning God regardless of source or intentions. In ecclesiastical experience, however, theology is nothing less than the very evangelical word of Christ, who ‘explains’ (John 1: 1-2) in the Spirit the things of the Father. And this ‘explanation’ does not consist primarily of an addition to the primordial metaphysical ‘great debate concerning being’ (the Platonic γιγαντομαχίαν περί τῆς οὐσίας). It is rather the proposal for our ontological introduction to a certain mode of existence through the Spirit, which occurs, according to St Nicholas Cabasilas, through the ‘Mysteries of the Embodiment’: Baptism, Chrism, the Divine Eucharist, and the attunement of our freewill by the grace they bestow. This ‘mode’ manifests the pre-eternal counsel of the Trinity within history for the eschatological gathering of Creation through its ecclesialisation in the human nature of its Creator, the enhypostatic God and Logos. Theology is manifested in this case as an imitation of Christ’s own consent to the Father’s loving good-pleasure. And in referring to imitation, we mean participation. Inasmuch as it is principally an event rather than a reductive intellectualism, theology is acted out in our burning desire, which responds to the divine unconditional desire that changes the rational creature’s mode of existence; it is the fruit, in other words, of our will-to-participation in the Eucharistic transformation of Creation in the Body of Christ. Thus theology can only be articulated as an ecclesialisation of language, as an expression of the Eucharistic transfiguration of the intellect, which in a doxological yet simultaneously critical fashion ecclesialises created concepts in light of the ‘obedience of Christ’, following the biblical-patristic sense of a right ‘discernment of spirits’.… Continue Reading

What is it that we call theology?

On an epistemological level, there is no doubt that the response seems easy: theology is every discourse concerning God regardless of source or intentions. In ecclesiastical experience, however, theology is nothing less than the very evangelical word of Christ, who ‘explains’ (John 1: 1-2) in the Spirit the things of the Father. And this ‘explanation’ does not consist primarily of an addition to the primordial metaphysical ‘great debate concerning being’ (the Platonic γιγαντομαχίαν περί τῆς οὐσίας). It is rather the proposal for our ontological introduction to a certain mode of existence through the Spirit, which occurs, according to St Nicholas Cabasilas, through the ‘Mysteries of the Embodiment’: Baptism, Chrism, the Divine Eucharist, and the attunement of our freewill by the grace they bestow. This ‘mode’ manifests the pre-eternal counsel of the Trinity within history for the eschatological gathering of Creation through its ecclesialisation in the human nature of its Creator, the enhypostatic God and Logos. Theology is manifested in this case as an imitation of Christ’s own consent to the Father’s loving good-pleasure. And in referring to imitation, we mean participation. Inasmuch as it is principally an event rather than a reductive intellectualism, theology is acted out in our burning desire, which responds to the divine unconditional desire that changes the rational creature’s mode of existence; it is the fruit, in other words, of our will-to-participation in the Eucharistic transformation of Creation in the Body of Christ. Thus theology can only be articulated as an ecclesialisation of language, as an expression of the Eucharistic transfiguration of the intellect, which in a doxological yet simultaneously critical fashion ecclesialises created concepts in light of the ‘obedience of Christ’, following the biblical-patristic sense of a right ‘discernment of spirits’.

In this sense, every form of authentic theology is contemporary or, as we say today, ‘contextual’. This indicates chiefly that this acted-out and never-ending event of gradual Eucharistic transformation of thought is expressed precisely as the assumption as gifts of all the created givens of human intellectuality, civilisation, science, etc. and their critical elevation to the possibility of their transformation in the Spirit into multiplicitous manifestations of the mystery of Christ. Put in another way, this event is a highly dynamic and creative activity, and should never be regarded as an apologetic for or defence of a mythologised or petrified ‘tradition’.

When these aforementioned criteria are met, theology naturally passes into its ‘communicative phase’, as Rowan Williams terms it, who goes on to further to define it as ‘a theology experimenting with the rhetoric of its uncommitted environment’.1 However, this communication in our era must be, first of all, intra-theological. Like von Balthasar, who never thought to dismiss his Barthian inspiration, or Pannenberg, who could not function without the synthesis of ‘Orthodox’ and ‘Roman Catholic’ sources in his ecclesiology, or Congar, De Lubac and Daniélou, who made the Greek Fathers an inseparable part of modern Roman Catholic theological awareness, modern theology needs to exist in dialogue. This real dialogue is, unfortunately, often far from being self-evident. For some representatives of the major Christian confessions, such an enterprise must bring about a kind of ultimate absorption, explicit or implicit, of any form of theological otherness, thereby rendering their own theological certainty unshakable. Centuries of alienation created isolated, ironclad identities in need of permanent theological support. It is supposed, for example, that Thomas Aquinas’ thought includes that of Gregory Palamas, Barth is more comprehensive than Maximus the Confessor, and Jonathan Edwards is more ground-breaking than John Chrysostom, etc.

Cultural submission, in the sense given to this concept by Arnold Toynbee, unfortunately seems to still be the unconscious ideal of some Western Christian theologians. It is still possible, for example, to read serious handbooks striving to give an account of twentieth century theology where Orthodox theology is not even mentioned, as if it never existed. 2 This is likely the case because some authors still insist in believing that there is nothing in Orthodox theology worth mentioning that is not already included in this or that Western theological sub-trend. Though things are rapidly changing today, confessionalism— a spiritual disease that touches theologians of all Christian confessions— is still the demise of any real theological communication. Nevertheless, it is absolutely possible to be Orthodox, or Catholic , or Protestant, and discuss theology since there are always better or worse theological expressions of the Christian experience. This discussion is not about who is saved by Christ or not (and it is good to know that Christ looks upon hearts and not upon good ideas), but about theologies to a greater or lesser degree facilitating or hindering salvation. Does this not provide sufficient ground for an honest theological communication?

On the other hand, postmodernity—the misfires of which are comprehensively described by Charles Taylor as a thoroughly self-sufficient humanism existing under the aegis of globalisation—provides some fundamental characteristics that can potentially be received positively, in a sense helping us move towards the aforementioned venture of a diachronic Eucharistic transformation of thought. When, for instance, post-modern philosophy casts doubt upon the existence of knowledge or truth as the exact replication of or a precise correspondence to reality, or objects to the idea of absolutely normative descriptions manifested through causes and distinctions that are hypothetically valid for all time periods, or resists any kind of supposedly objective ethical philosophy combined with the great narratives laying claim to a global perspective, is it not in juxtaposition to the onto-theological equalising of metaphysics in a certain sort of Scholasticism, which culminates in the Hegelian abrogation of every difference through a unity that actually murders every form of otherness? The same can be said of the critique of metaphysical rationalism as well as of the influence of the Enlightenment and the idols of social rationalism, which, according to Horkheimer and others, reinstates the social function of religion. Even when post-modern thinkers like Derrida, Foucault, Lyotard, Deleuze, and Vattimo as well as Searle and the other members of the analytic school resist every transcendental presupposition of thinking, they can perhaps also be read as intending to re-evaluate the real, which has sank beneath the metaphysical domination exercised by the modern transcendental subject.

Moreover, on an anthropological level, the critique of the transcendentality of the subject has resulted precisely in the discovery of the somatic roots of the conscience as well as the innate communality arising from human nature. The students of Marx, Darwin, Freud, and Nietzsche discovered, conversely, the domination exercised upon the supposedly free transcendent Ego of Western Idealism by the coercive and absolute referentiality in the communal and natural realms. This referentiality embeds the subject in economic relations and/or in an unconscious world of instincts supported by its unavoidable somatic underpinning. Additionally, the referentiality of this kind of consciousness to the things of this world offered phenomenology— from Husserl to Marion and, in our own era, Kearney— a means of founding the subject directly in intersubjectivity, bringing along with it all of the outstanding problems associated with intersubjectivity’s ontological grounding.

Despite the fact that (and, also, precisely because of it) we do not underestimate the accompanying problems that post-modernity created—beginning with the abrogation of nearly all common sources of meaning that determine, according to Castoriades, the ‘social imaginary’, to the deconstruction of the subject, which occurs, as Besnier observes, either ‘from above’, through the social sciences analysing modern collectives , or ‘from below’, through the discoveries of neurobiology —we are bound to say that there has never been such a time when the hour of theological inquiry was so imminent for the West. It is up to us at this juncture to take advantage of the post-metaphysical—or, better, the beyond-metaphysical—and post-ontological—or, more accurately, the beyond-ontological, as we are yet able to use the expression ‘ontology’—capacity of Christian theology to see enhypostatic nature fundamentally as a relationship between created and uncreated. This is a relationship that is constituted by dialogical reciprocity between created and uncreated. Consequently, enhypostatic nature as an open relationship is likely one of the most valuable gifts Christian theology can offer to Western thought today, which is exhausted by the ruptures between body and soul, matter and spirit, person and nature, transcendence and immanence, individual and person, history and eschatology, etc.

Apart from philosophy, a discussion must forthwith be extended also in the direction of psychology and sociology. Fundamental terms and dimensions within these fields—the meaning of selfhood or of social formation, for instance—must be discussed in a way that will bring mutual benefit. The same approach can be taken in relation to the contemporary theory of the state. Christian theology has the capacity to make a particularly significant contribution to the endeavour to locate an anthropocentric foundation for political theory. It is of the utmost importance that there also be engagement with the contemporary natural sciences and biology. Here theology can, though it may seem hyperbolic or paradoxical, contribute to the articulation of the methodological presuppositions of these scientific disciplines. And, naturally, theology is also capable of making a rather remarkable contribution to the theory of art.

Orthodox theology in particular can assist in bringing about these objectives and in engaging these various intellectual perspectives in a decisive way. Of course, it goes without saying that such engagements, along with many possible others, would enable modern theology to illumine hitherto undiscovered corners of Christian experience, and turn discussion in the direction of new and unexpected horizons.

As the mission statement clearly indicates, this new Journal seeks to assist in the inauguration and promotion of discussions like those mentioned above. First and foremost, its goal is the facilitation of a dialogical Christian self-understanding in this seemingly meta-Christian world. Strangely enough for the heirs of the Enlightenment, this world still longs for a Christianity illumined by the Spirit. Orthodox theology, with its unbroken tradition, deserves a place in this dialogue. And no one doubts this today. It is therefore of the utmost significance that this academic Journal is sponsored by the Holy Great Monastery of Vatopedi, one of the largest, most ancient, and traditional monasteries of the Holy Mountain. Since its establishment more than a thousand years ago, this Monastery has given the Church dozens of canonized Saints, great Patriarchs, Bishops, and famous scholars as well as great works of philanthropy, education, and art.

It is therefore appropriate that this Journal takes its point of departure from Mary, the Theotokos, the most venerated person, after the Triune God, on the Holy Mountain, the Garden of the Panagia, as it is called by its inhabitants. Mariological theology is extremely rich in both East and West, and the articles of this issue aspire to catch a glimpse of this theology’s splendour. Starting from the New Testament, Dr Karakolis’ article gives an excellent account of Christ’s deep spiritual communion with his mother, demonstrating the uniqueness of Theotokos’ role in Divine Economy. Archimandrite Ephraim, the Abbot of Vatopaidi, offers an excellent panorama of the patristic literature concerning the Virgin’s sinlessness, correcting some modern theologians’ views concerning this matter. Dr Andreopoulos suggests a re-interpretation of the Areopagite’s description of Mary’s funeral, connecting it with the deeply Eucharistic dimension of Patristic theology. Dr Cunningham provides an exceptional essay on the connection of the Theotokos with the natural world in the Byzantine patristic sources. Prof. Bronwen Neil offers us exciting new material concerning the role of the Theotokos as selective intercessor for souls in Middle Byzantine apocalyptic literature. She concludes by proving that ‘the theme of Marian discrimination in intercession reflects an anti-Judaism found in some Marian hymns and homilies of the early Byzantine period, such as sixth-century Ephesus, but is not the standard in the hymns and homilies of John of Damascus, Andrew of Crete, or Germanos of Constantinople’. Dr Tsironi gives a convincing account of the Palamite affinities of Anthony Bloom’s Marian theology. Finally, I strive to articulate a modern systematic discussion of Cabasilas’ and Bulgakov’s hesychastic mariological humanism in dialogue with the contemporary theological and philosophical adventures of humanistic ideas.

-Nikolaos Loudovikos, Senior Editor

1.On Christian Theology (Oxford: Blackwell, 2000), xiv.

2.See, for example, the massive and erudite work by Rosino Gibellini, La Teologia del XX secolo (Bres-cia: Editrice Queriniana, 1992). Contrast this with David Ford, ed., The Modern Theologians: An Introduction to Christian Theology in the Twentieth Century, 2nd edition (Oxford: Blackwell, 1997).

The Dormition of the Theotokos and Dionysios the Areopagite

Much of the hymnography and the tradition surrounding the Dormition of the Theotokos have been based on a passage from the Divine Names of Dionysios the Areopagite, which includes the phrase ζωαρχικόν καὶ θεοδόχον σῶμα. This phrase was read by John of Scythopolis as a reference to the Dormition, and subsequent scholarship never questioned this until recently. In recent years, however, this reference has been questioned repeatedly. This article examines the significance of this issue and this confusion for Eucharistic and for Marian theology.

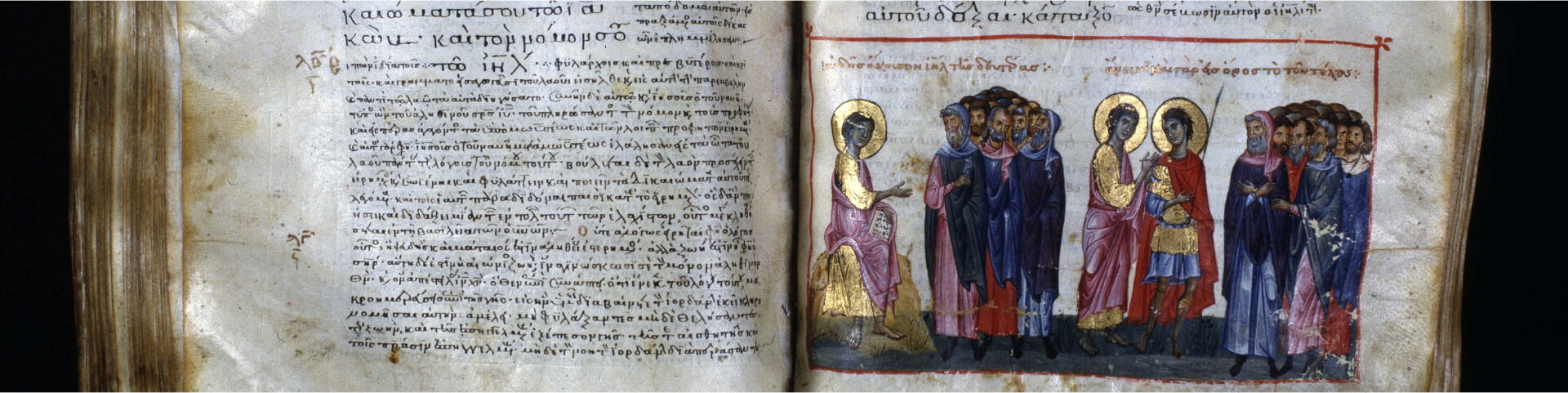

Strange as it may sound, we derive much knowledge by accident and error. We can sometimes receive an insight on a certain process by noticing what it is being confused with, as it develops. Inscriptions or documents with misspelled words for instance, allow us to understand how pronunciation is changing, and how when we start finding the name of Matthew the Evangelist spelled as Ματθέος instead of Ματθαῖος (such as in the sixth-century mosaic of St Catherine’s on Sinai), we realize that there is no phonetic difference between ε and αι anymore. Naturally, we can find many such examples in the manuscript tradition, some of which may not be very important or meaningful, whereas others sometimes lead us to serious mistakes. In a strangely similar way, what I am going to talk about here is largely what can be thought of as a theological misspelling, which may likewise allow us to make some observations about the development of early Christian spirituality and the developing cult of Mary.

Before we proceed with the study of the historical or theological misspelling though, let us take a wider look in order to establish the field. Our field of observation starts with the feast of the Dormition. Much work has been done on the textual and theological origins of the feast itself (mostly the impressive work of Stephen Shoemaker on the subject 1), and we have a fair idea of the way the significance of the feast developed from a more general Marian celebration to a feast that focusses on the historical—even if apocryphally attested—death of Mary, even if the theological implications of that particular death transcend history. The Dormition in the iconographic tradition is often portrayed on the western wall of a church, as the last image that the faithful see on their way out, a reminder of their own mortality and the hope of their salvation by Christ. In this way, Mary is presented as a model for all humanity, even in her death.

Practising Consubstantiality: The Theotokos and Ever-Virgin Mary between Synergy and Sophia in St Nicholas Cabasilas and Sergius Bulgakov, and in a Postmodern Perspective

This paper examines the in-depth way Nicholas Cabasilas assimilated Palamite Hesychastic theological anthropology, transforming it into a Mariological humanism of theological provenance, which responds to the humanism of the Western Renaissance. Then it compares it with an analogous tendency in Bulgakov’s thought, putting this theological humanism in dialogue with the self-sufficient humanism of the post-modern kingdom of man.

A Long Introduction: Byzantine Individualism and Hesychasm

According to the experts, the conflict between the iconoclasts and the iconophiles, which ended in the victory of the latter, seems to present a key to the interpretation for the understanding of the spiritual state of Byzantium in the period that Paul Lemerle refers to as the ‘first Byzantine humanism’ in his eponymous book.1 This era spiritually preceded and somehow inaugurated the period that Steven Runciman calls the ‘second (or last) Byzantine Renaissance/Humanism’,2 the period during which St Nicholas Cabasilas lived. The essence of the matter is that the icon defends the completeness of human nature and of the world against the likelihood of an Eastern (Semitic and Asian) ‘blending’ of this nature in the ocean of the divine nature. In this sense, the spiritual purview of icon veneration (apart from being the locus where a distinctive eschatological ontology was consolidated, the significant theological and philosophical consequences of which have yet to be studied) also provided a home for a humanism which, apart from anything else, preserved certain fundamental requirements of classical Greek education as well as the whole of medieval ‘Greek’ Aristotelianism.

1.In the ‘historical’ pages which follow an attempt is made to construct a critique of the works of specialists. See particularly P. Lemerle, Le premier humanisme byzantine. Notes et remarques sur enseignement et culture à Byzance des origines au Xe siècle (Paris: P.U.F., 1971); C. Mango, Byzantium, The Empire of New Rome (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1980); H. G. Beck, Das Byzantinische Jahrtausend (München: O. Beck, 1978); S. Runciman, Byzantine Civilization (London: Edward Arnold, 1959); S. Runciman, The Last Byzantine Renaissance (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1970; H. Ahrweiler, L’ideologie politique de l’Empire Byzantin (Paris: P.U.F., 1975).

2.This also, not coincidentally, functions as the title of his book, The Last Byzantine Renaissance.

The Mother of God and the Natural World: Byzantine Conceptions of Sacrament and Creation

This article examines the connection between Mary, the Mother of God, and a transfigured natural world, as depicted in Byzantine liturgical texts and experienced in the lives of Orthodox Christians. Although these two aspects of Marian devotion may seem unrelated, they both reinforce the Virgin Mary’s theo-logical role as the meeting-place between the divine and created spheres. Byzantine hymnography and homiletics use typology not only to express Mary’s role as the receptive creation into which God entered, but also to convey a sacramental meaning specifically linking the Theotokos with the mysteries of baptism and the Eucharist. More tangible reminders of her link with the material elements that play a part in spiritual renewal and healing can be found in the shrines, often endowed with miraculous pools and springs, that existed in medieval Constantinople. Both formal liturgical and popular association of the Theotokos with a transfigured creation thus reinforced her role as Christians’ main intercessor before God in the Byzantine world.

Hail, favoured one, the all-gold jar of manna and the tabernacle truly made of purple, which the new Bezaleel adorned in golden style! Hail, favoured one, forever purple God-bearing cloud and spring eternally pouring out grace for everyone! 1 …

Praise of Mary, the Mother of God, takes many forms in Orthodox liturgical worship. Passages such as the above, which appear not only in surviving Byzantine festal homilies but also in the hymnography that is still sung in offices of the great Marian feasts, may bewilder a visitor who encounters this tradition for the first time. Instead of instructing the faithful in a discursive or literal way by means of lessons and sermons, the Orthodox Church presents congregations with a fully developed exegetical interpretation of Scripture, much of which is expressed by means of prophecy, typology, and song (often the biblical canticles). Such didactic practice, which is especially espoused in the Eastern Christian tradition, must reflect a belief that the Christological mystery is best expressed by means of poetic, and especially biblical, language.

1.Germanos, Homily on the Annunciation, in D. Fecioru, ‘Un nou gen de predica in omiletica ortodoxa,’ Biserica Ortodoxa Romana 64 (1946): 71; trans. M. B. Cunningham, Wider Than Heaven. Eighth-Century Homilies on the Mother of God (Crestwood, NY: SVS Press, 2008), 226.

The Palamite Background in the Marian Theology of Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh

Perceptions of the Mother of God have always reflected theological and pastoral concerns of Orthodox theologians and thinkers in Byzantium and beyond. Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh, one of the em-blematic figures of the Russian Diaspora, treats the Virgin in a way that reflects the main concerns of his generation, marked by the political developments in Russia in the beginning of the twentieth century and the subsequent movement of the Russian Diaspora. The hardship of the loss of their homeland and the harsh reality of poverty, as well as the two world wars, greatly influenced the theological approach of Metropolitan Anthony and his generation. In his talks and homilies, Anthony of Sourozh focuses on the human person cut off from the community and its rituals. He speaks about the encounter of the individual with God on a one-to-one basis. He refers extensively to the agony man experiences when faced with the silence of God. He sees the Virgin as the model of the obedient but not passive disciple, the model of the dynamic surrender to God in freedom and sorrowful joy. Anthony’s approach to the Mother of God is paralleled and compared to that of Gregory Palamas, who in the fourteenth century saw Mary as the model of perfect Hesychast.

Throughout Christian history, the Mother of God has been the vehicle for the expression of various aspects of Christian theology, formulated in literature, homiletics, and art. Her reception from the early Christian era down to our times reveals aspects of contemporary concerns and approaches to Christian doctrine. A great figure of the Russian Diaspora, Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh, is one of the eminent personalities who have marked Orthodox theology with their work in the 20th century. His approach to Patristic theology has been very different from the approach of other theologians of his era, like Metropolitan Kallistos Ware, Metropolitan John Zizioulas, Christos Yannaras, Fr Andrew Louth, and others. Each of the aforementioned figures contributed a distinct understanding of Christianity that enriched Orthodox theology and its reception in modern times.1

The Theotokos as Selective Intercessor for Souls in Middle Byzantine Apocalyptic

The Apocalypse of the Holy Theotokos, first edited from a single manuscript in 1866, has only recently become available in an English translation and commentary. However, the work enjoyed enormous pop-ularity in the later Byzantine period of the fourteenth to sixteenth centuries, when the Greek text was translated into almost a dozen other languages. An equally popular work of the mid-tenth century was the Vision of Anastasia. This paper considers Mary’s role in the two Apocalypses of the ninth to eleventh centuries in the broader context of Byzantine apocalypticism of the period. In particular, I focus on Mary’s role as a selective intercessor for Christian souls in torment, but not Jews. The increasing recognition of Mary’s humanity in the cult of the Theotokos (Mother of God) emerges as the justification for her discrim-ination against those who were perceived as the murderers of her son.

This paper considers Mary’s role in two Apocalypses of the ninth to eleventh centuries in the broader context of Byzantine apocalypticism of the period.* The Apocalypse of the Holy Theotokos has recently become available in an English translation and commentary by Jane Baun. Selections of this text were edited from a single manuscript, Venice Marc. VII.43 in 1866. Its relative inaccessibility to scholars does not reflect the enormous popularity of the work in the later Byzantine period of the fourteenth to sixteenth centuries, when it was translated into almost a dozen other languages, including a sixteenth-century Romanian version and Old Church Slavonic versions, as well as medieval Greek.3

*Some of this material has been included in my chapter ‘Mary as Intercessor in Byzantine Theology’, The Oxford Handbook of Mary, ed. Chris Maunder (Oxford: Oxford University Press, forthcoming).

1.Jane Baun, trans., Tales from Another Byzantium. Celestial Journey and Local Community in the Medieval Greek Apocrypha (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 391-400. This paper was originally presented at the conference on The Theotokos in the Oriental Churches, 18-20 August 2015, University of Winchester, UK.

2.Konstantin von Tischendorff, ed., Apocalypses Apocryphae Mosis, Esdrae, Pauli, Iohannis, item Mariae dormitio, additis Evangeliorum et actuum Apocryphorum supplementis (Leipzig, 1866; repr.. Hildesheim: G. Olms, 1966). A completed edition followed, made from Paris BN graecus 390, by Antoine Charles Gidel, ‘Étude sur une apocalypse de la Vierge Marie’, Annuaire de l’association de l’encouragement des études greques 5 (1871): 92-113. Another two editions appeared in 1893, the first in Athanasius Vasiliev, ed., Anecdota graeco-byzantina. Pars prior (Moscow: Imperial University, 1893; repr., Moscow, 1992), 125-34, and the other in Montague R. James, ed., Apocrypha Anecdota. A collection of thirteen apocryphal books and fragments, Texts and Studies 2.3 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1893), 109-26, the latter edition based on Oxford Bodleian Library MS Auct. E.5.12 (olim Misc. Greek 77).

3.See Baun, Tales from Another Byzantium, 37.

The Sinlessness of our Most Holy Lady

Following the Third Ecumenical Council, the assimilation of the dogmatic teaching about the Theotokos was very slow. Certain Fathers were waypoints regarding the person of the Theotokos, such as Cyril of Alexandria, John Damascene, Gregory Palamas, Nicholas Kavasilas, Nikodimos the Athonite, and Silouan the Athonite.In this paper, we compare the positions of certain contemporary Orthodox theo-logians with those of the previously mentioned Fathers regarding the subject of the sinlessness of the Virgin Mary.

Let no uninitiated hand touch the living Ark of God’, we sing at the ninth ode of many of the feasts of the Mother of God. Indeed, the mystery concerning the person and the life of the Mother of God is a book ‘sealed with seven seals’1 for the uninitiated, for those who do not have the revelation, the divine grace. It is a real and audacious mystery, divine and human, inaccessible to those with feet of clay. How can anyone understand the most sublime matters concerning the Mother of God, since he or she does not even have experience of lesser things? How can anyone who has not been purged of the passions speak with authority about deification?…

The Gospels are silent regarding the life of Our Lady, the Virgin, and reveal only very little. But the Holy Spirit, with the Tradition of the Church, teaches us a great deal, such as the significance and meaning of the Gospel references. And the Mother of God herself often reveals information to her faithful servants, the Fathers of the Church.

In the beginning, the Church was not greatly concerned with formulating dogma about Our Lady. It did so only as regards the Triune God (Trinitarian dogma) and the incarnate Word (Christological dogma). The dogmatic teaching of the Church concerning Our Lady was formulated gradually, in direct correlation with Christology. It was only the Roman Catholic Church which formulated particular doctrines about Our Lady (immaculate conception, the assumption of her body, etc.). Thus, Saint Basil the Great, within the perspective of the ancient patristic tradition and addressing those who had doubts about the virginity of the Mother of God after she gave birth, shifted the significance of the matter onto the virgin birth of Christ, and said that virginity was essential until the incarnation, but that we should not be curious about afterwards because of the mystery involved.3

*Literally ‘outside the temple’ therefore ‘uninitiated’, which is what the hymn says, rather than the modern meaning of ‘irreverent’. [trans. note]

1.Rev 5:1.

2.Basil the Great, Εἰς τήν ἁγίαν τοῦ Χριστοῦ γέννησιν 5 (PG 31:1468ΑΒ).

3.See Chrysostomos Stamoulis, Θεοτόκος καί ὀρθόδοξο δόγμα. Σπουδή στή διδασκαλία τοῦ ἁγίου Κυρίλλου Ἀλεξανδρείας (Thessaloniki: Palimpsiston, 1996).

The Mother of Jesus in the Gospel according to John: A Narrative-Critical and Theological Perspective

This study attempts to analyse the narrative function and the theological significance of Jesus’ mother for the overall theology of the fourth gospel, mainly based on the exegetical method of narrative criticism.In the first part, the problem of the anonymity of Jesus’ mother in juxtapposition with the anonymity of the beloved disciple is dealt with. The second part consists of a detailed exegetical approach to the narrative of Jesus’ first sign in Cana within the Johannine narrative context as a whole. On this basis, in the third part a response to further relevant questions about the significance of Jesus’ mother according to the overall fourth gospel’s witness is attempted. The article is concluded with a summary of exegetical and theological positions, including a hypothesis about a possible Johannine background of the current Orthodox understanding of Theotokos.

The fourth evangelist presents the mother of Jesus quite differently from the synoptic gospels. Specifically, he never mentions her name, and omits the nativity stories altogether, although apparently having some knowledge of at least parts of the synoptic tradition.1 Instead, he refers to her in two incidents that are unknown to the synoptic gospels, namely the miraculous change of water into wine at Cana of Galilee (John 2:1-11), and her presence along with the beloved disciple at the foot of the cross (John 19:26-27). Through these two stories the fourth evangelist apparently complements the synoptic tradition and at the same time interprets it anew. The obvious question arising from these observations regards the particular significance of the ‘mother of Jesus’ in the Johannine narration and theology. In my attempt to answer to this question, I will base my analysis on a relatively new method in New Testament studies, namely narrative criticism.2

1.For the problem of John’s knowledge of the synoptic tradition, see for instance Ian D. Mackay, John’s Relationship with Mark: An Analysis of John 6 in the Light of Mark 6–8, WUNT 2/182 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2004); John Amedee Bailey, The Traditions Common to the Gospels of Luke and John (Leiden: Brill, 1963); Andrew Gregory, ‘The Third Gospel? The Relationship of John and Luke Reconsidered’ in Challenging Perspectives on the Gospel of John, WUNT 2/219, ed. John Lierman (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2006), 109–134.

2.On the use of narrative criticism in New Testament studies, see for instance James L. Resseguie, Narrative Criticism of the New Testament. An Introduction (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic Press, 2005).